The third in our series of readers’ stories comes from Esther Sahle who is currently researching early modern Quaker merchants for a PhD at London School of Economics.

The third in our series of readers’ stories comes from Esther Sahle who is currently researching early modern Quaker merchants for a PhD at London School of Economics.

I have been asked to write about my experience of using the Library of the Society of Friends. I could give a very short answer to this…it’s great. It’s everything you could wish for as a researcher, a friendly, peaceful place. I’m working towards a PhD about early modern Quaker merchants, and in the three years that I’ve been doing research, I have received more support here than at any other institution. I’ve been visiting the Library regularly and it’s always been a very pleasant experience.

I knew very little about Quakers when I started. Visiting the Library changed this very quickly. It appears to contain copies of everything ever written by and about Quakers, from the 17th century until today. And it’s so easily accessible. There are friendly and expert staff who appear to know everything about Quaker history. It’s great to be able to ask a librarian about literature on a certain subject and, from off the top of their head, be directed to relevant resources. The cherry on top is that when you need a break from reading, the café at Friends House does excellent cappuccinos.

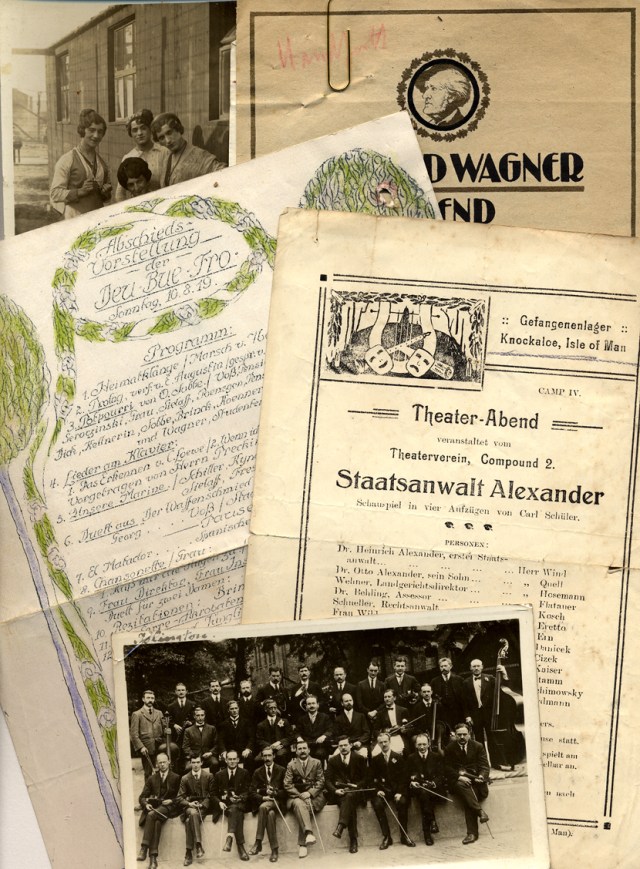

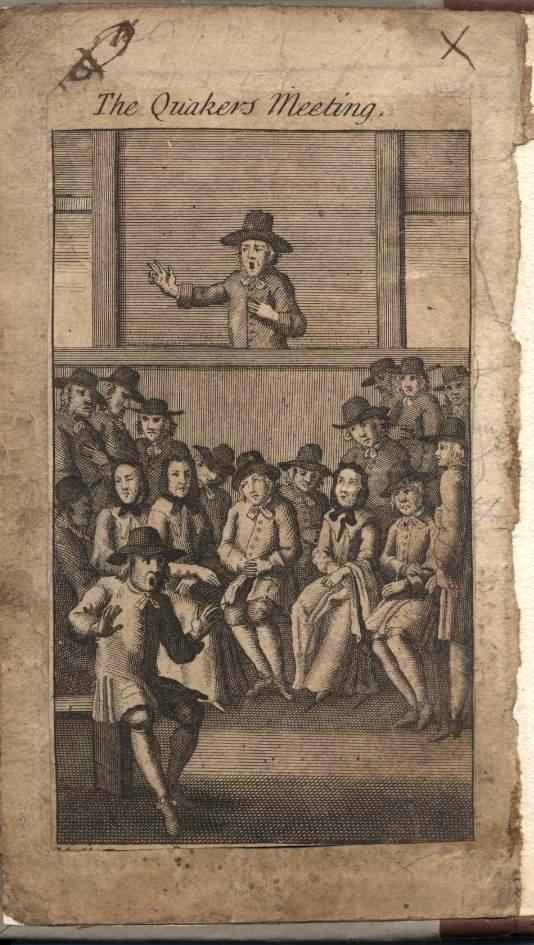

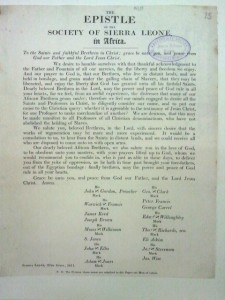

The Library is a place that provides knowledge and wisdom on everything to do with Quaker history. However, it does much more than that. Quakers formed an important part of society in early modern London. Even though small in numbers, the community played an important part in the social and economic development of the city. The manuscripts held by the Library on the lives and businesses of London Quakers allow the reader to view early modern London through the prism of Quaker experience. I traced the lives and activities of merchants from the late 17th to 18th centuries. From the minutes of Quaker meetings, I followed how young Friends moved from other parts of the UK to London, in order to take up apprenticeships with city merchants; how they later got married to women whose families resided in Pennsylvania or Barbados; how they took their young children on daytrips to the countryside; how their careers developed; and how they appeared as officers in their meetings, and after them their places were taken over by their sons and grandsons.

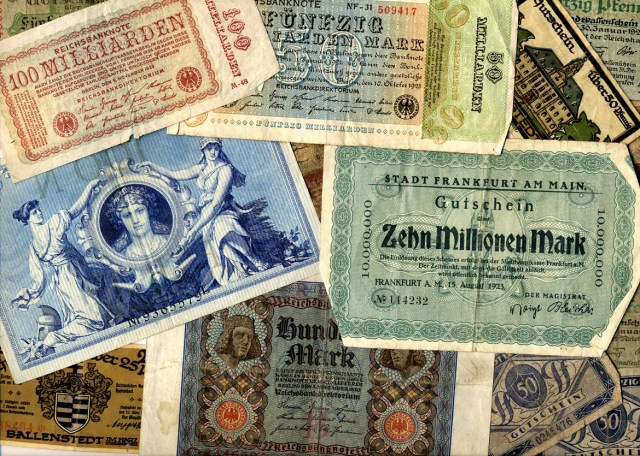

I saw how communities dealt with fraud and theft. An enlightening case is that of George Roberts of Ratcliff Monthly Meeting, who in 1729 lured several respectable citizens into investing in his laboratory in Southwark, where he planned to turn base metals into gold. The investors lost their money and Roberts was disowned for falsely pretending to have skills in alchemy. No comment was made on the fact that alchemy in general might not work.

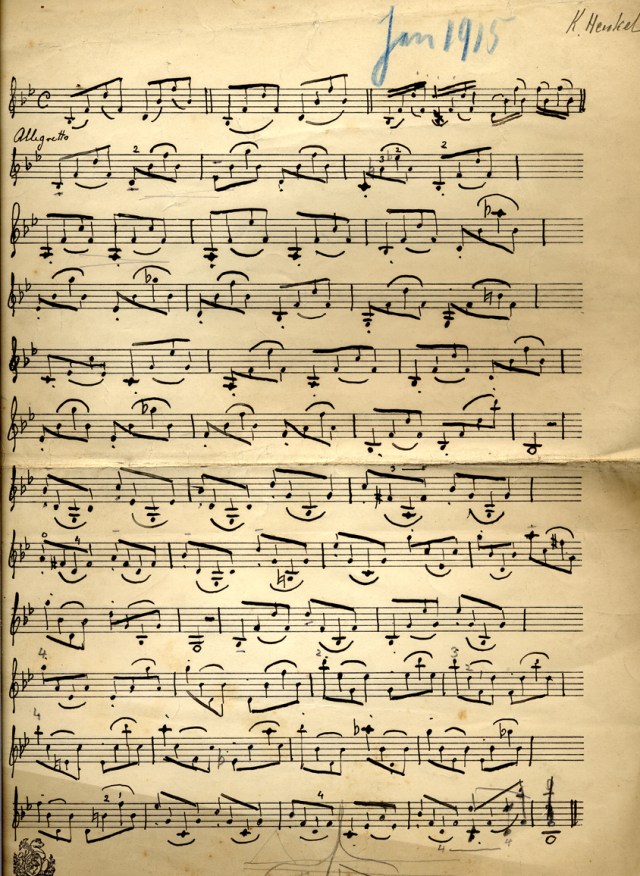

During my research, I found that I recognized addresses, places and family names, and found that their concerns were similar to ours today. They worried about their families, current affairs, and the challenges of an increasingly materialistic society. They were sometimes bored at work, as indicated by the doodles on the margins of the 17th century manuscripts. But they also lived in a world in which alchemy was a possibility. This reveals their London, however familiar, simultaneously to be like a foreign country, with a distinct culture, which is hard for us to understand. The manuscripts held at the Library provide us with the opportunity to get as close to this place as possible. The handwriting we read in 2013 consists of ink applied to paper by individuals, 300 years ago. It puts us in touch with them, with the London of 1700. We see the differences, but also the astonishing amount of similarities, between their lives, and ours. Between the London of then, and of today. And thereby, the Library becomes not just a source of academic knowledge, but an immediate access point to our own past and the roots of our own culture and identity.