‘Imagine a second hand bookshop in a Derbyshire garden, and the bookman a fine old Quaker, lovable at sight, interesting withal, and himself the best book in his collection – a living book about books.’

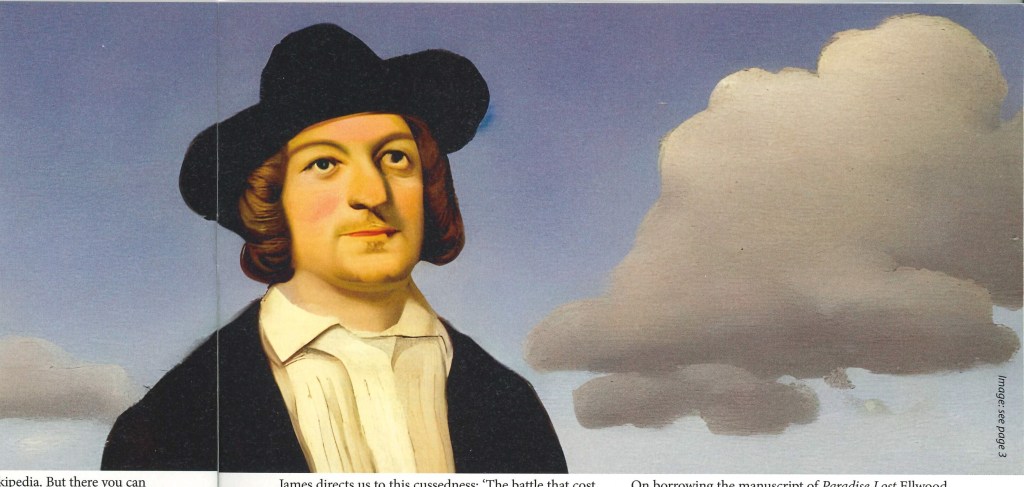

For Bookshop Day tomorrow, we thought we’d celebrate an undersung Quaker bookseller, Henry Thomas Wake, whose archives we hold at the Library. The quote above is from a visitor to his Fritchley bookshop in 1912, not long before Wake died. While there, the visitor viewed Wake’s beautifully hand-drawn catalogues and observed ‘You should have been an artist’. At this, Wake replied casually ‘That’s what Ruskin said.’ Wake had known not only the eminent Victorian art critic in his youth, but also Thomas Carlyle, whose bookplate he designed. How had this engineer’s clerk from a modest background ended up mixing in such illustrious circles?

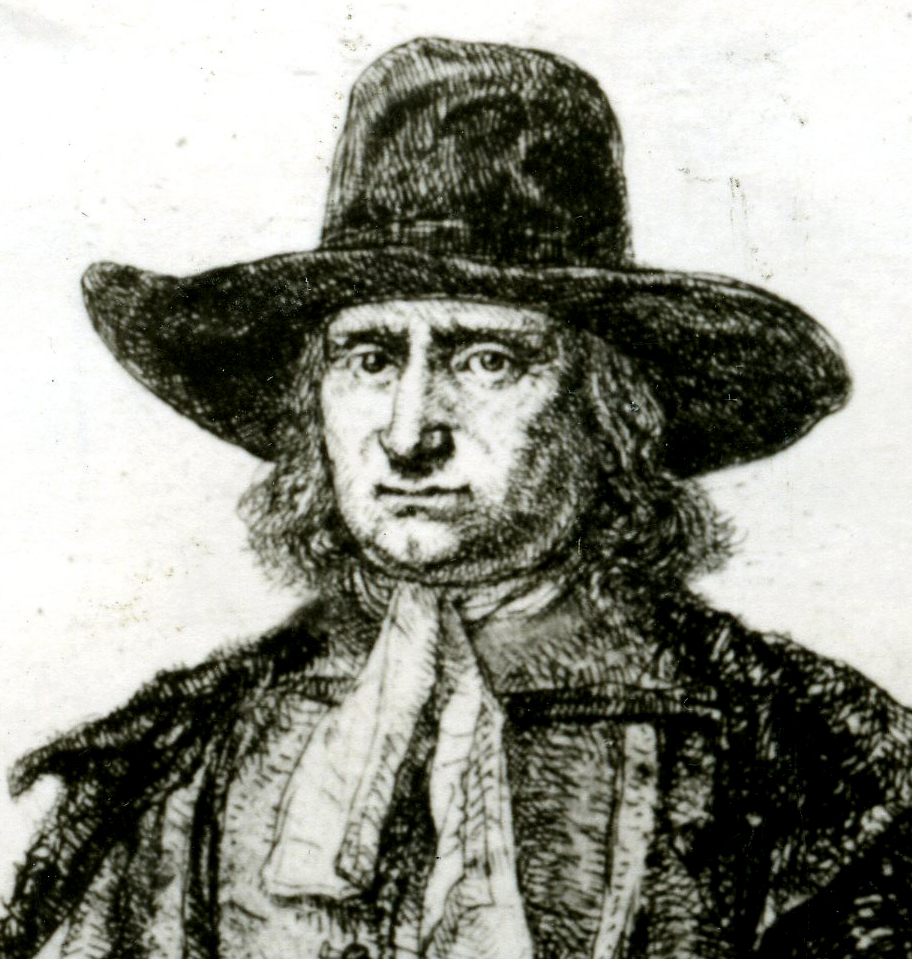

Wake was born to a Methodist family in Northamptonshire in 1832. A bright boy, he went to grammar school and eventually to London as a teenage clerk in various banking and shipping companies. Due to his low income, university wasn’t available to him, he nonetheless took advantage of the many opportunities for self-education that were springing up in the Victorian city. He was open and curious, attending the London Institution regularly, reaching out to Thomas Carlyle after he had read Sartor Resartus (impressed by the passages on Quaker founder George Fox). He visited one of Carlyle’s welcoming soirées, meeting Carlyle and his wife Jane. They bonded over English civil war memorabilia – Wake was already a budding antiquarian – and Carlyle commissioned a bookplate from Wake.

His curiosity also took him to his local Friends’ Meeting House – Brook Street in Ratcliff – where he was an attender for two years before he was admitted as a member of the Society of Friends in 1856, at the age of 25. However, even before this, Carlyle felt he was already losing his new friend: ‘There is clearly nothing to be made of that Grampus Wake: the leather jerkin of George Fox has buttoned him up from the sight of Sun and Moon,’ he lamented to John Ruskin who also knew Wake.

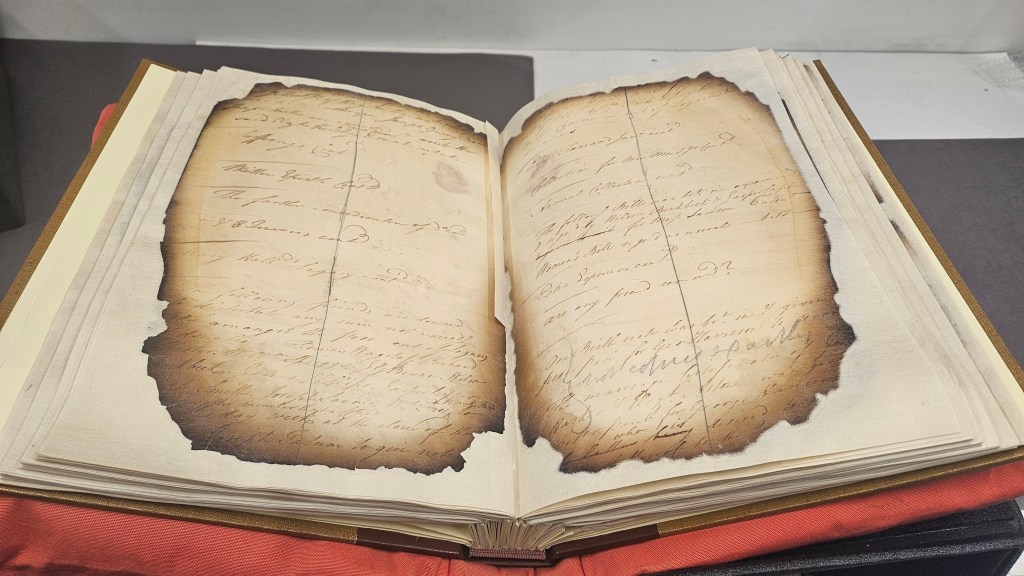

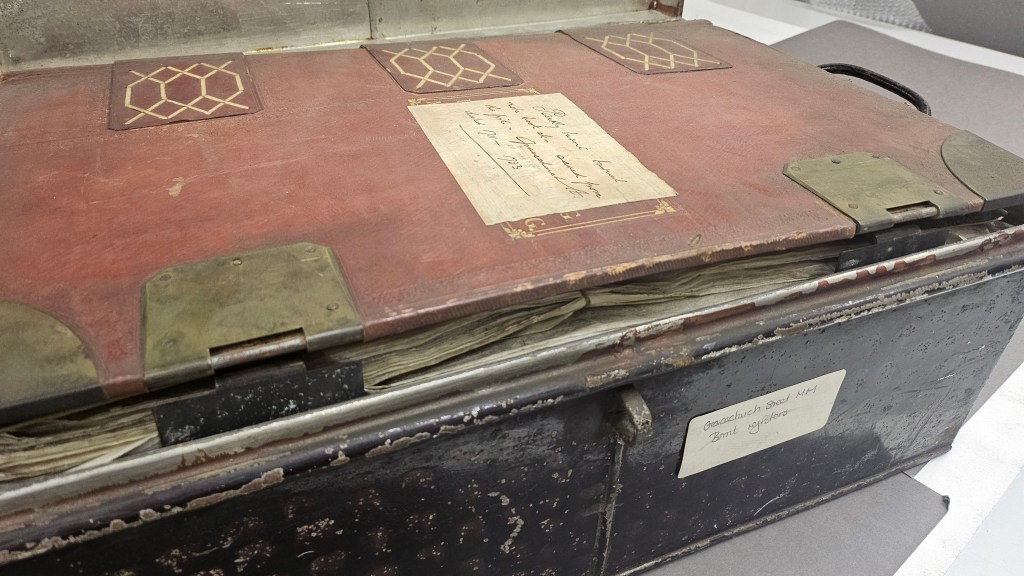

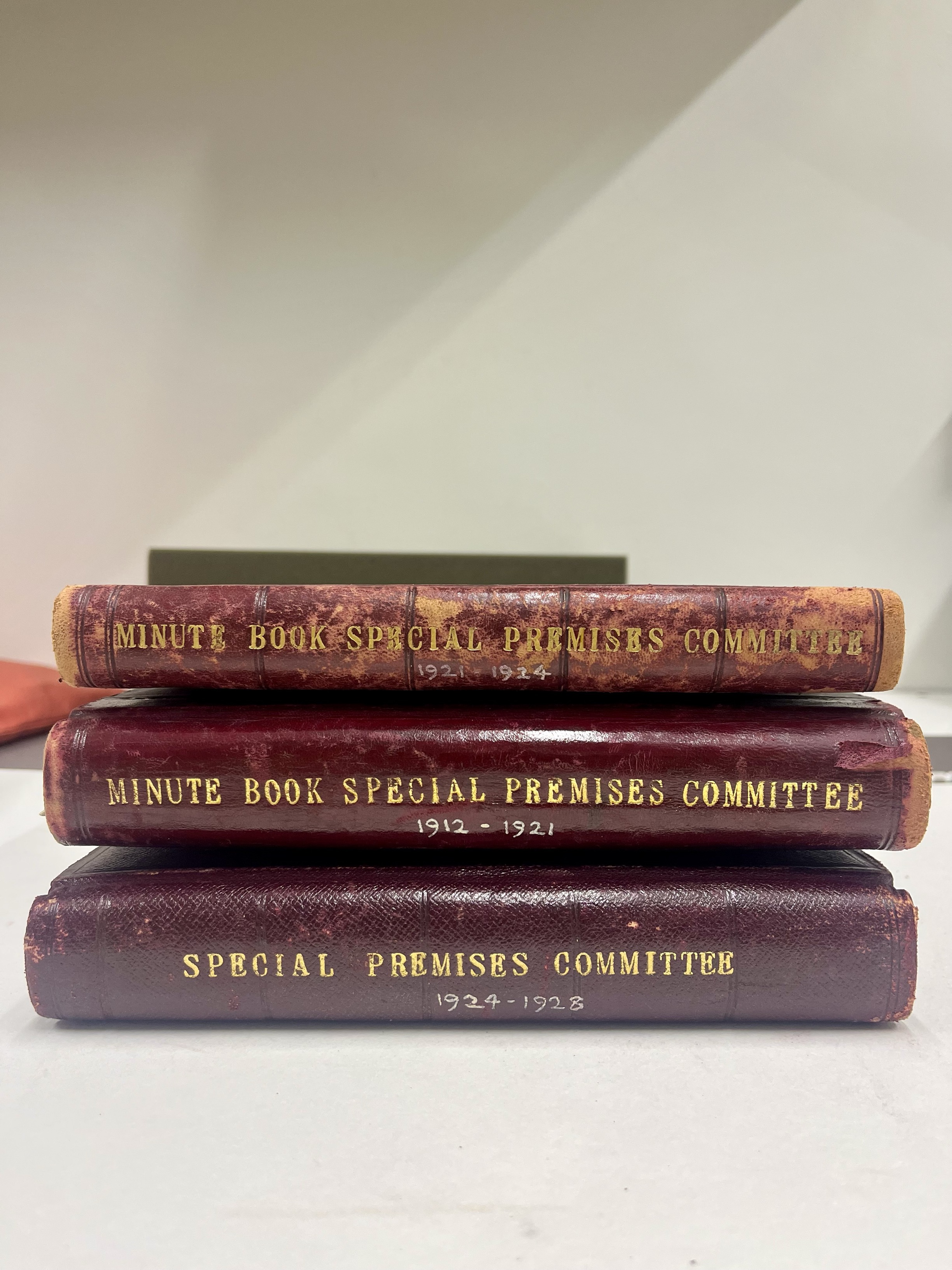

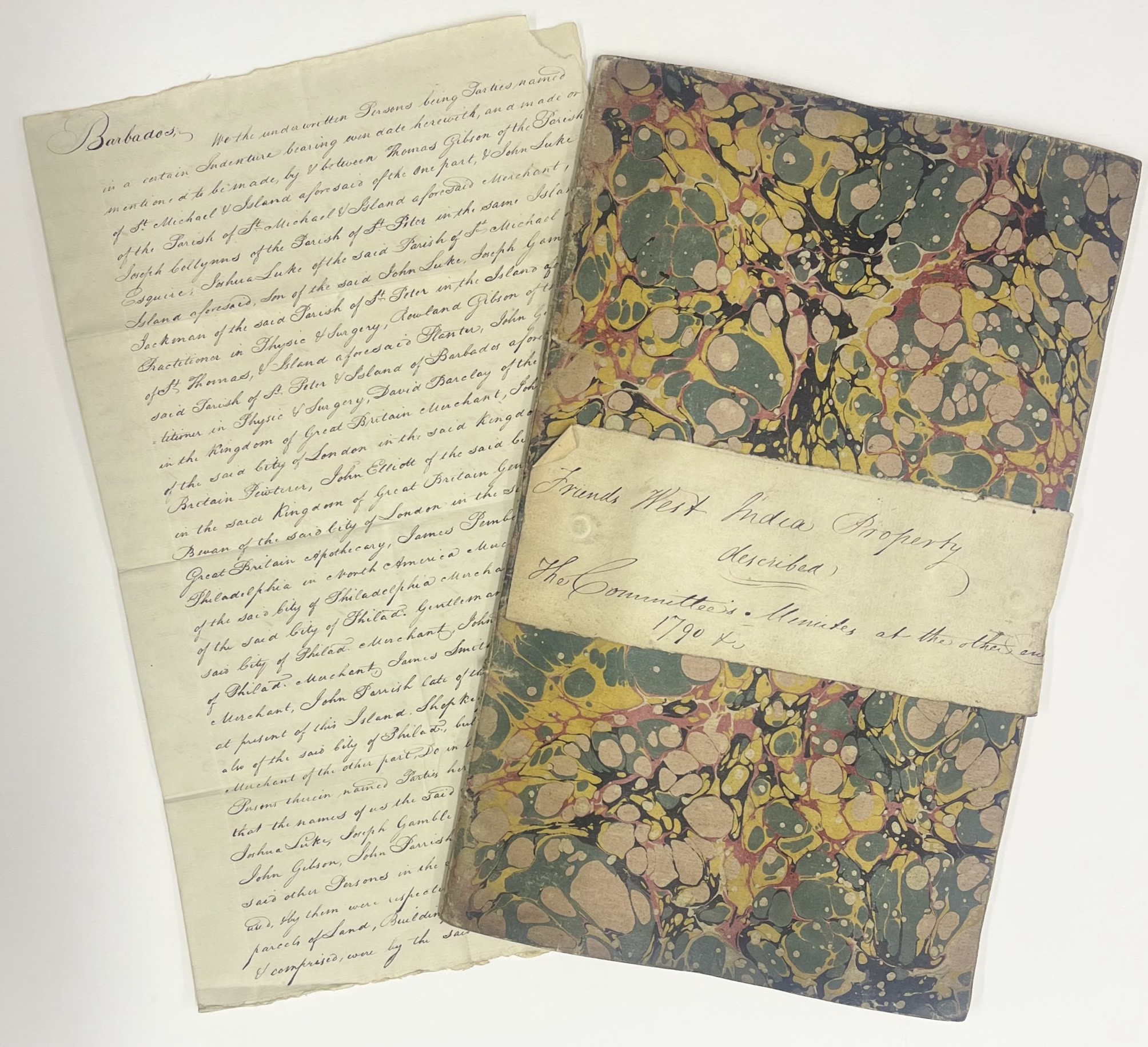

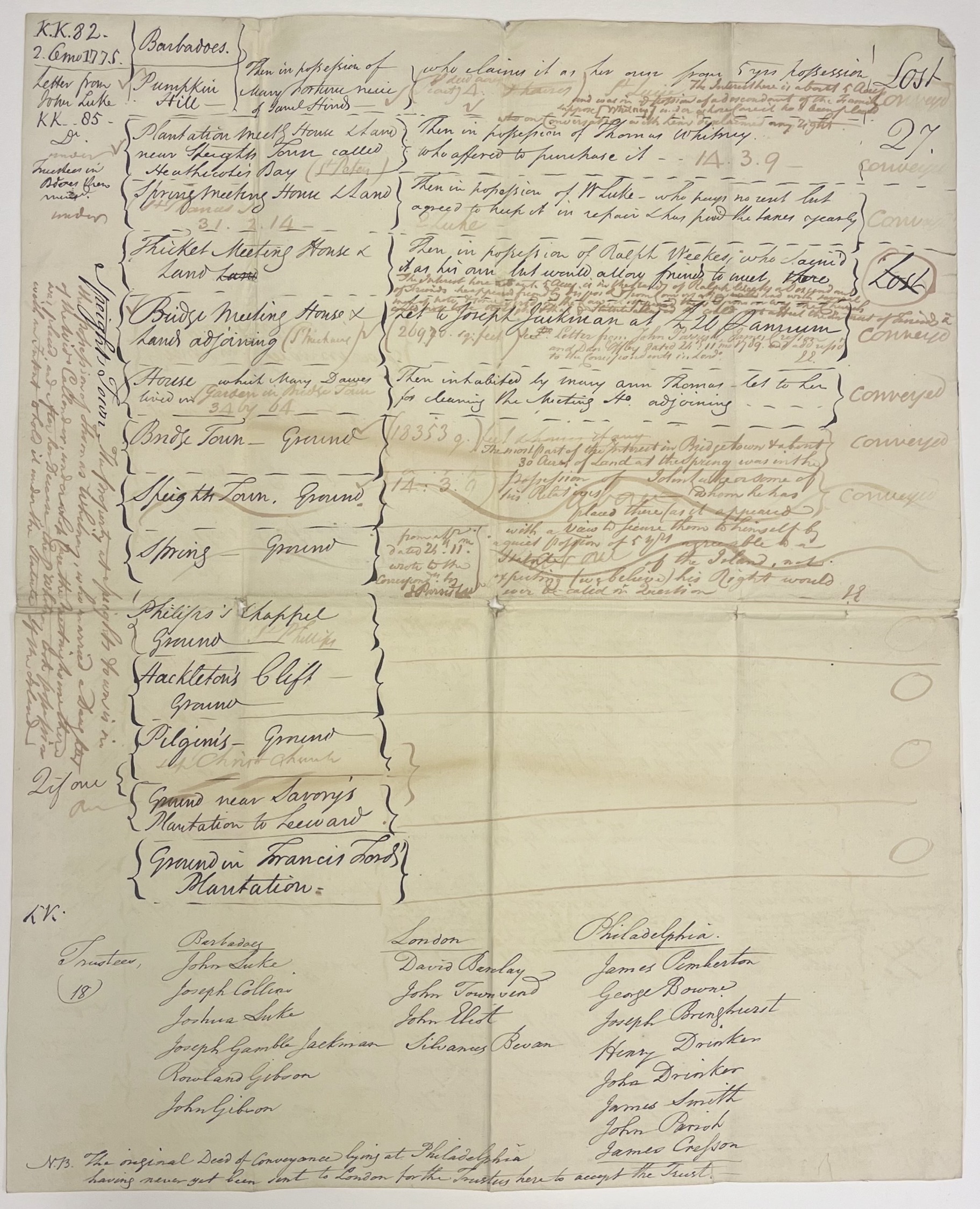

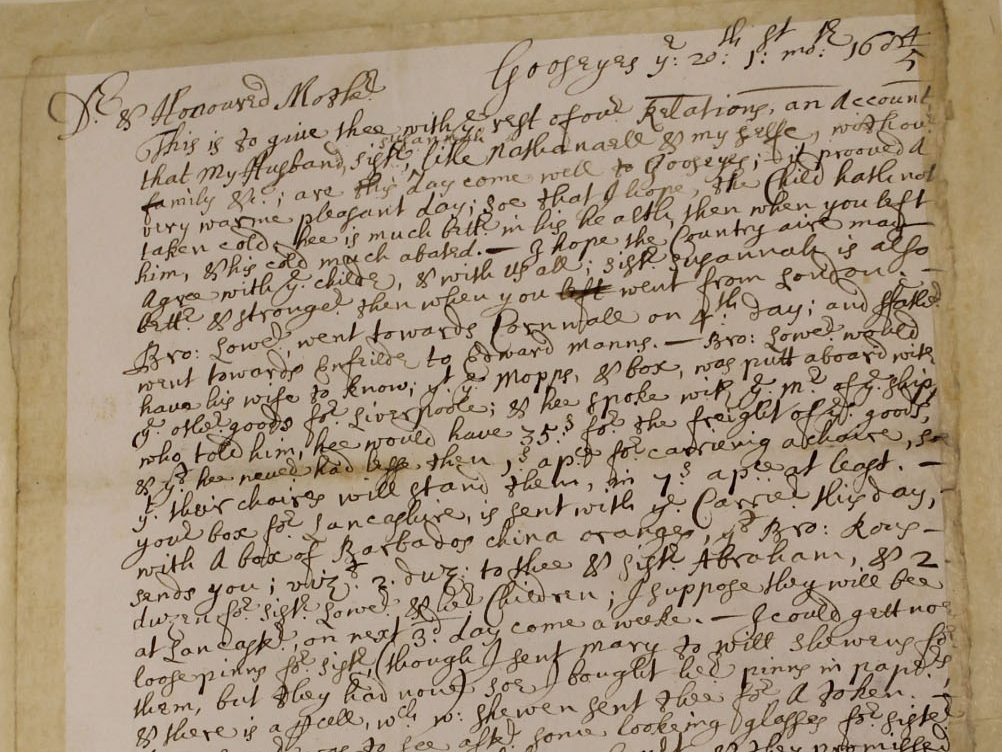

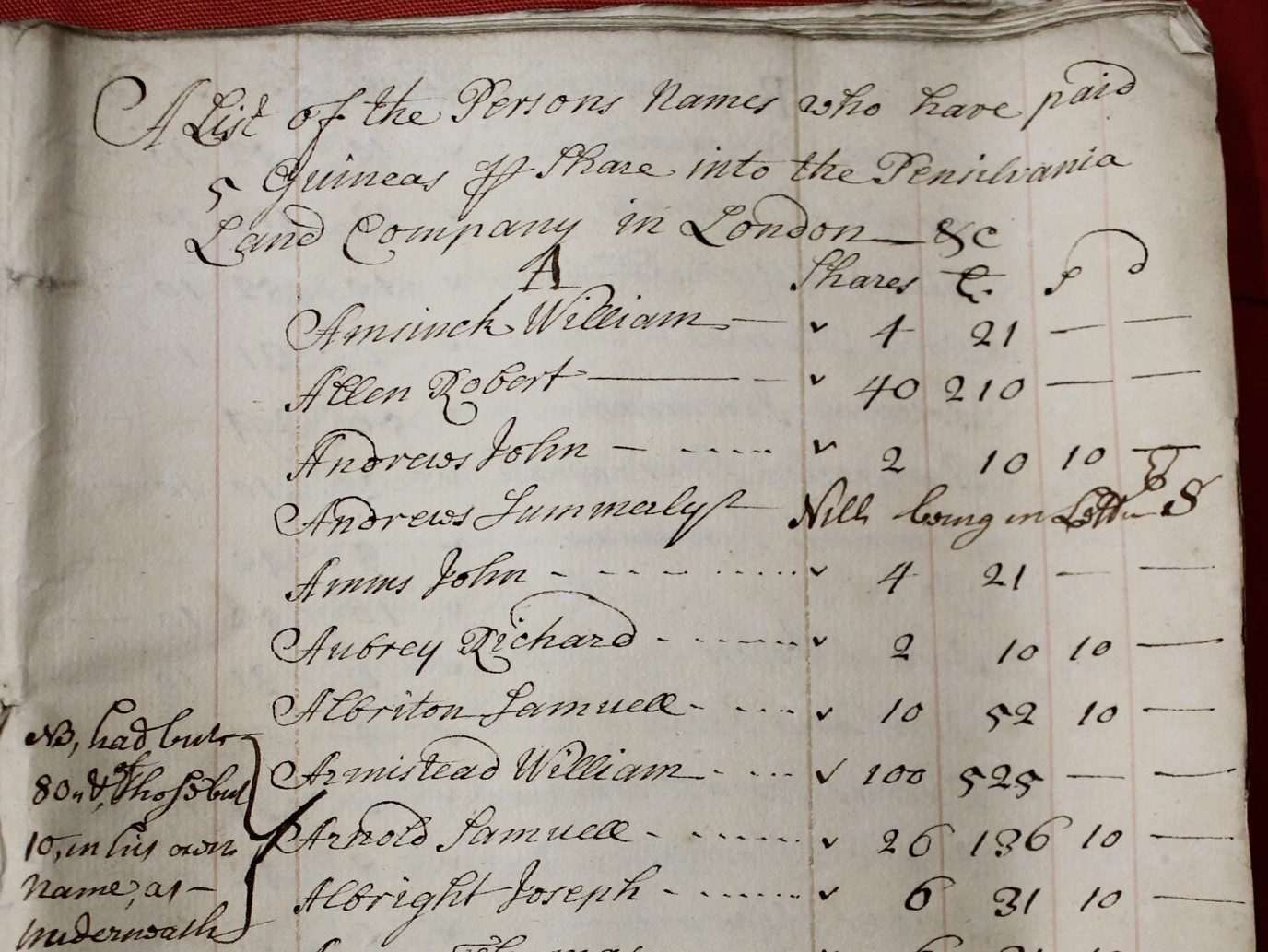

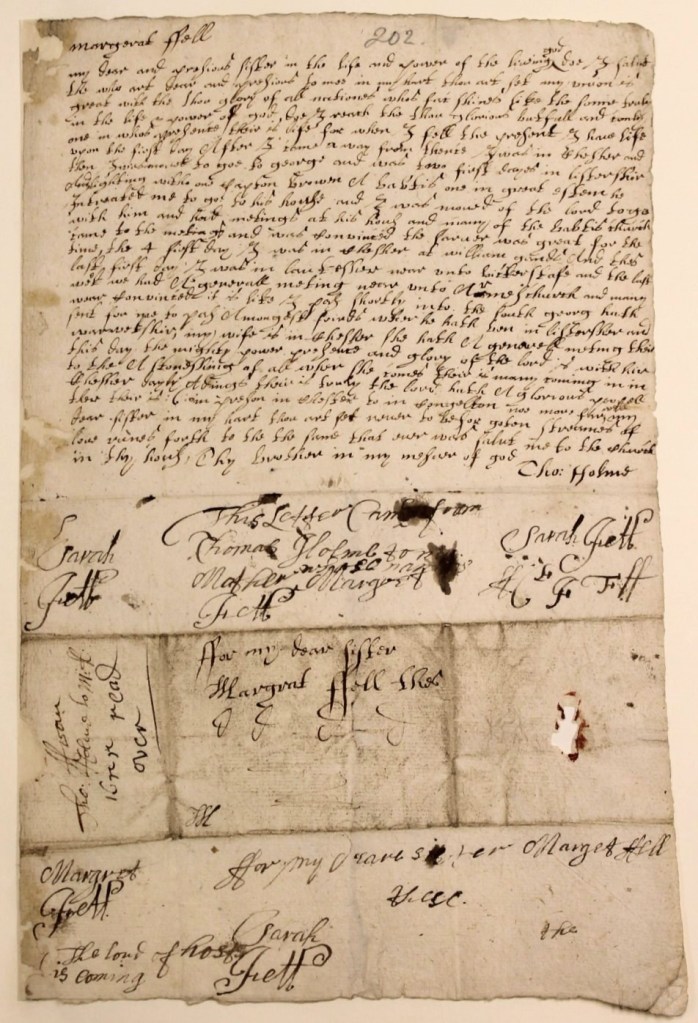

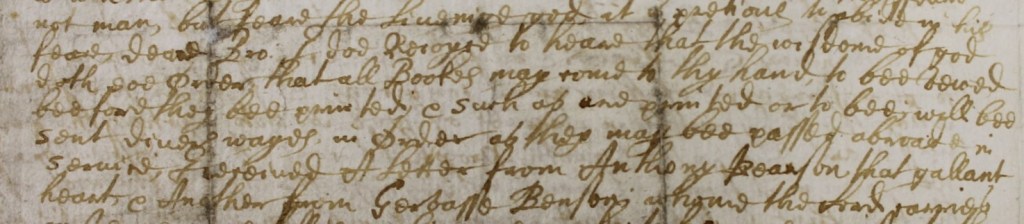

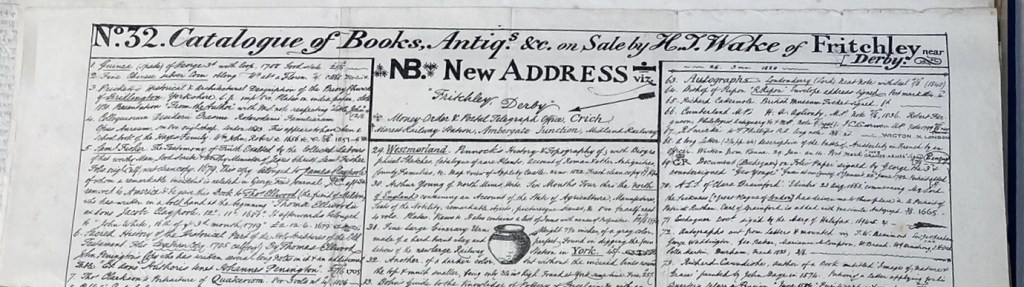

By this time Henry had also met and married a distant cousin, Lydia Carter, and had a growing family. Only a few years later they all left London and moved north, to the cradle of Quakerism – Cumbria – where he became a tutor. He continued his sideline as an antiquarian and bookseller, becoming also a dealer in manuscripts. He began to create exquisitely illustrated catalogues of items for sale, hand-lettered, with many small images of star items. A bound volume of these catalogues is held by the LSF.

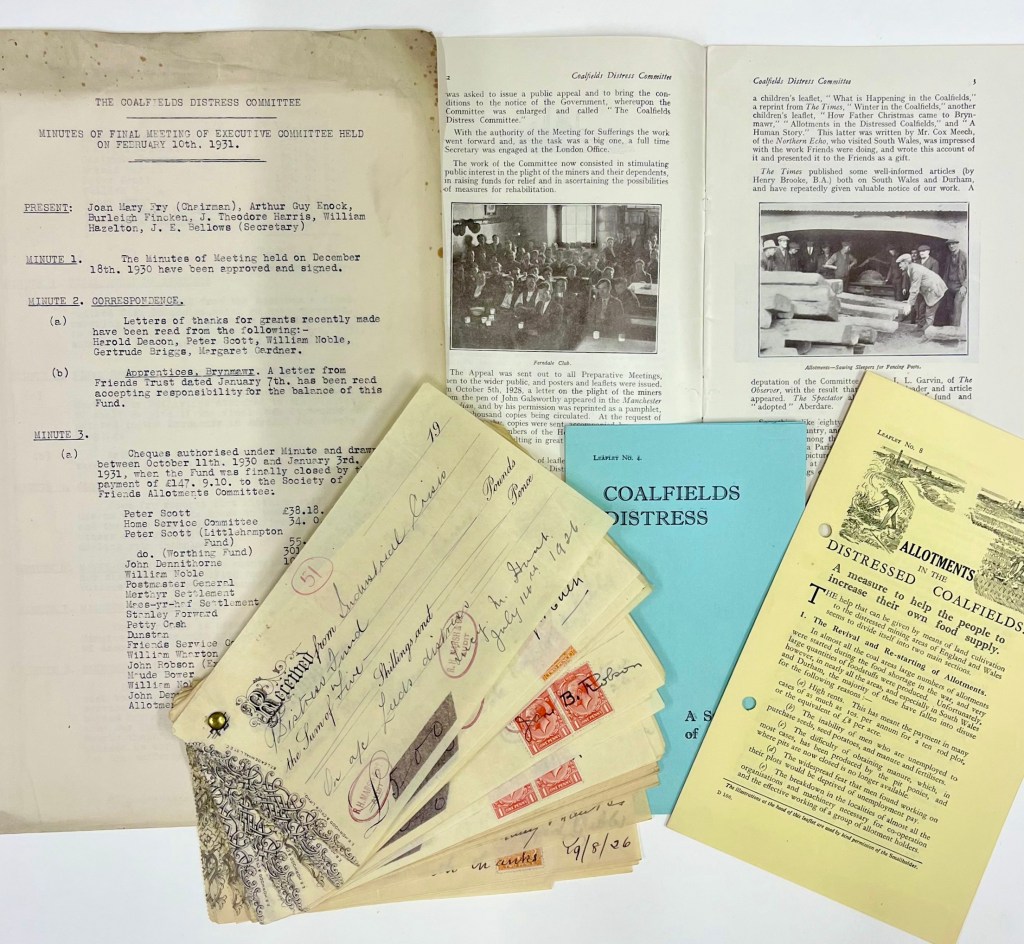

Also at the Library are Wake’s personal diaries and sales ledgers, which were always overlapping records: at first his personal journal recorded sales he made, and later the diaries became sales ledgers, which still included many personal notes, and the same charming illustrations that could be seen in his catalogues.

More mundane things like a pair of new boots might share a page with a recently acquired antiquity. They also contained more poignant personal notes, such as when Wake’s wife Lydia died in 1876, he recorded this in worked-over font, expressing his depth of emotion.

He was left with three children still under 14, and as was often the case with widowers with young children, was mindful of finding them another carer to share the load of their upbringing. By this time, he had been living in Cockermouth, Cumbria for more than ten years, but we see from his catalogues that some time in the middle of 1879 (three years after Lydia’s death) he moved to Belper in Derbyshire. A clue to the reason for his move might be found in his marriage in August of that year to Hanna Sadler in nearby Matlock. From Belper he moved the following year to Fritchley.

Fritchley, a small village in Derbyshire, has an inversely outsize place in British Quaker history. Following liberalisation around dress and language in the mid-nineteenth century there was some reaction amongst more conservative Quakers . This led to some schisms within the faith, more pronounced in the US than in the UK. Fritchley meeting, led by newcomer to the area John S Sargeant decided to break with London Yearly Meeting (as the national organisation then was), and chose to keep to old-style simple dress, and language. They sent no representatives to LYM and only rejoined the main body of Quakers in 1967.

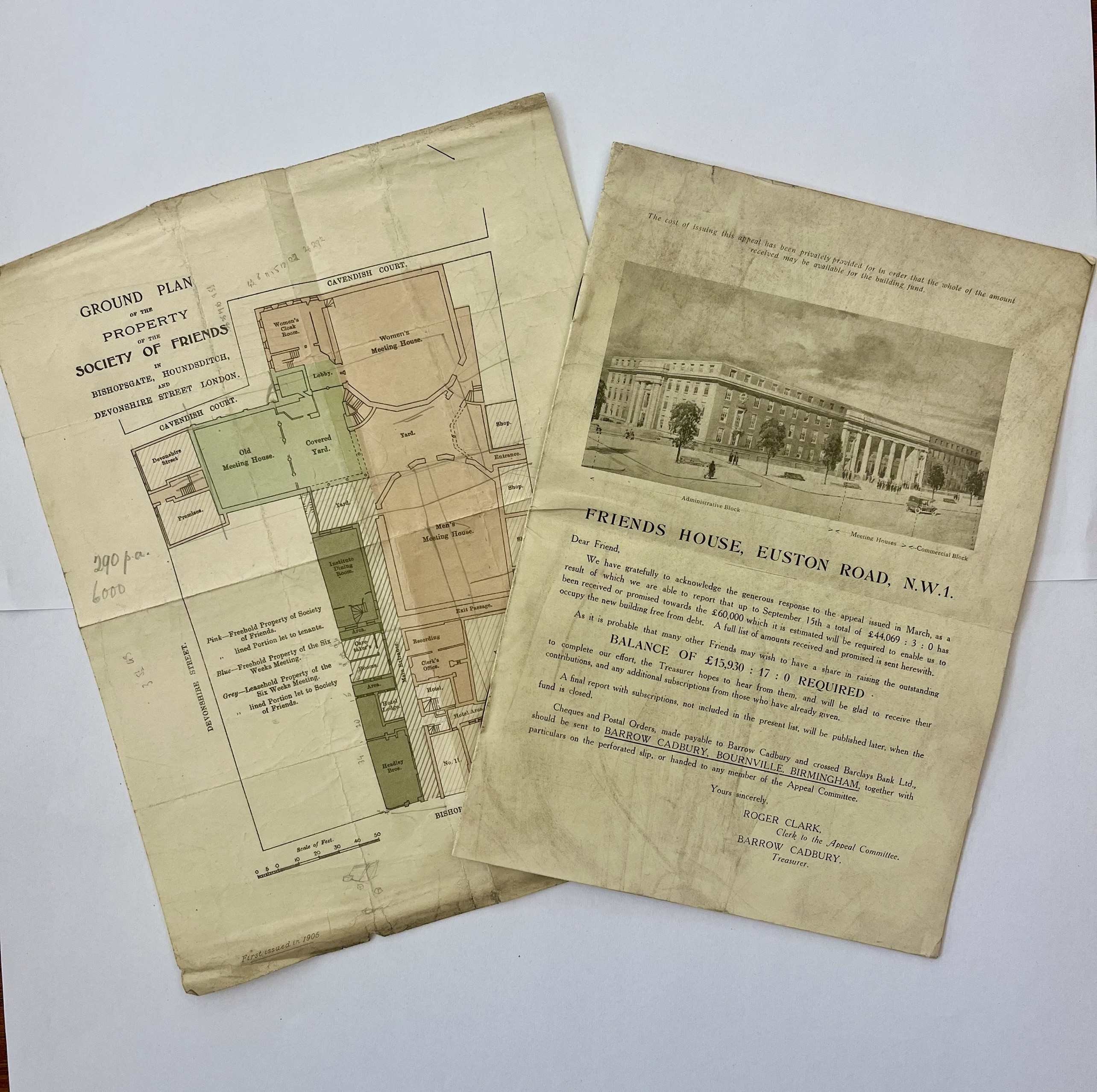

Perhaps as one who came to Quakerism rather than being born into the faith – those new to any belief system often being known for their zealousness – Wake found himself drawn to Fritchley. He ended up living at ‘The Chestnuts’ or ‘Chestnut Lodge’, designed by local Quaker architect Edward Watkins. It was a large set of buildings that served as a school with a home attached, which Wake occupied with his wife Hannah. It was from here that he supplied the Library (then at Devonshire House in Bishopsgate) with some key treasures in our collection, including a volume of letters of early friends in the handwriting of early Friend, William Caton, as well as being part of the chain of custodians of a rare copy of De imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ) by Thomas à Kempis, published at Milan in 1488. There was clearly more behind the unassuming frontage of a Fritchley bookshop than met the eye. Not only did the abovementioned visitor receive a cup of tea from Hannah Wake, but on expressing an interest in Thomas Carlyle, also received one of his letters to take away along with his haul of books. Hannah had persuaded her husband to part with it by pointing out forthrightly ‘We’ll not live more than twenty years anyway.’

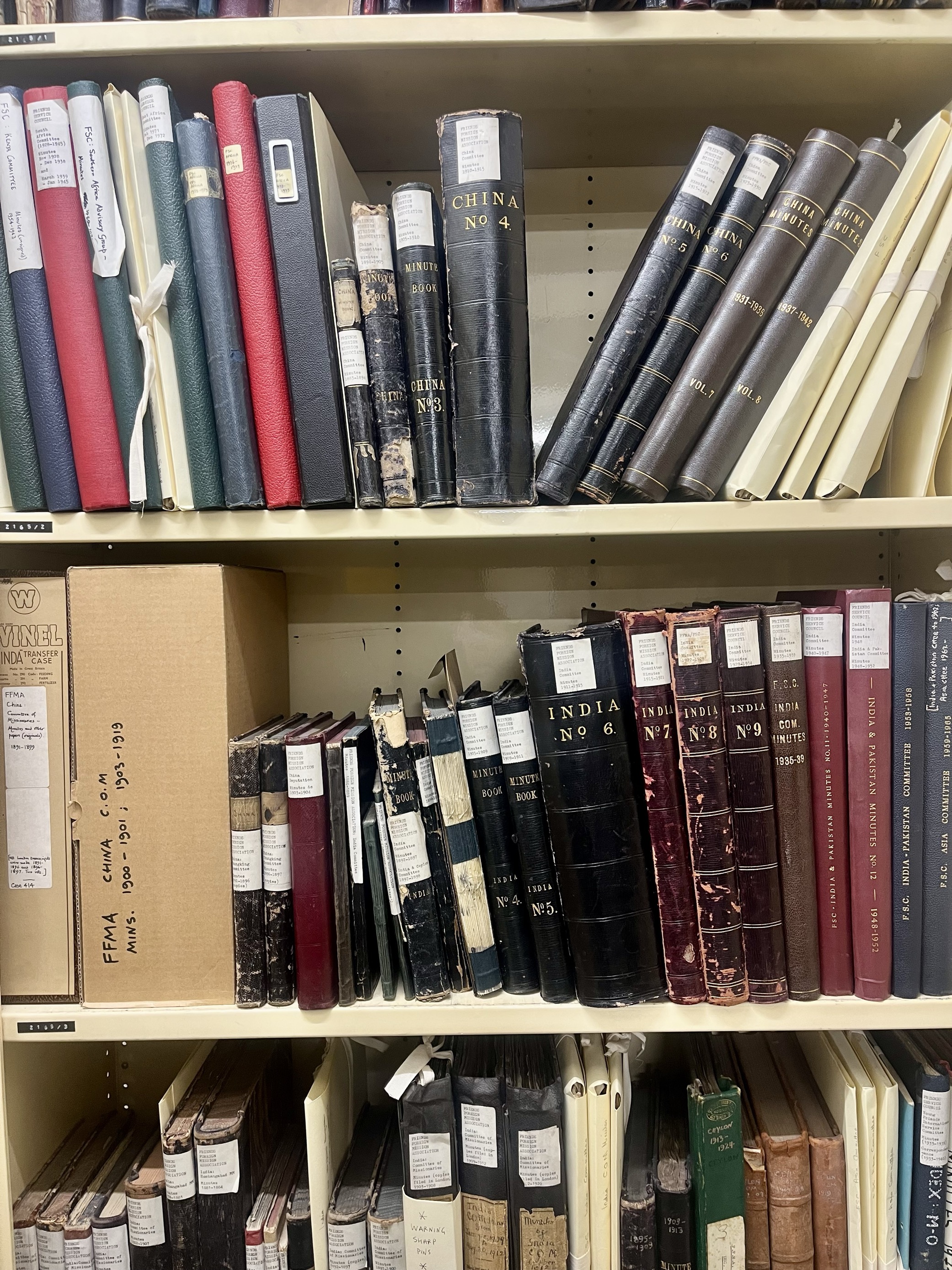

Sadly she was right at least about her husband. Henry Wake died a year or so later on the eve of WWI, with many of his descendants already emigrated to Canada. However, he is well memorialised at the LSF as we have many of his wonderful catalogues bound on the shelves, along with his journals and illustrated sales ledgers. Some are too fragile to handle, but all are on microfilm and available as PDFs.

Henry Thomas Wake papers https://quaker.adlibhosting.com/Details/archive/110013775

Carlyle’s bookplate and its designer : with several hitherto unpublished letters and unique Carlyle relics / by Davidson Cook https://quaker.adlibhosting.com/Details/fullCatalogue/64973

Catalogue of books, manuscripts, drawings, coins, autographs, old china, curiosities, &c. on sale at the cash prices affixed by Henry T. Wake https://quaker.adlibhosting.com/Details/fullCatalogue/70269