If you are interested in 18th century Quakers, there is one person you are almost certainly going to come across at some point – Dr John Fothergill. He was at the centre of Quaker activity throughout his life, involved with peace, prison reform and poor relief projects. He also made significant contributions in medicine and botany and his list of friends and acquaintances reads like a who’s who of the 18th century. The Library has a significant collection of his correspondence and other archival material about him, as well as copies of many of his published works.

Dr John Fothergill. Print published by Edward Hedges, 1781 (Library ref: MS Vol 337/67)

John Fothergill was born in Wensleydale in 1712 into a well-known Quaker family. Both his grandfather and great-grandfather had been imprisoned in York for refusal to pay tithes, and his father was a well-travelled “publick friend”. John himself remained a faithful member of the Society of Friends until his death in 1780, serving as clerk for London Yearly Meeting, paying for the publication of the Purver Bible (the “Quaker Bible”), and founding Ackworth Quaker school.

Ackworth School (Library ref: Pic Vol II/185)

He had initially seemed destined to be an apothecary, apprenticed to the Quaker Benjamin Bartlett at Bradford. Bartlett quickly recognized his pupil’s ability, however, and suggested that he attended medical school instead. As a Quaker, Oxford and Cambridge were closed to him, so he attended Edinburgh University, graduating in 1736 and then moving to London to practice.

Studying at Edinburgh instead of the English universities initially put the young doctor at a professional disadvantage – he was ineligible for a fellowship of the Royal College of Physicians – but he went on to become one of the most successful and well-respected doctors of his day. His writings on angina, diphtheria, trigeminal neuralgia (also known as Fothergill’s Disease), and migraine were considered groundbreaking and he gave the first known lecture on mouth-to-mouth resuscitation.

His medical opinion was respected. He was considered for the role of Royal Physician, but his religious beliefs ruled him out. When Catherine the Great was looking for a British doctor to inoculate the Imperial court against smallpox, it was Fothergill that the Russian ambassador approached, and Fothergill who recommended his friend Thomas Dimsdale.

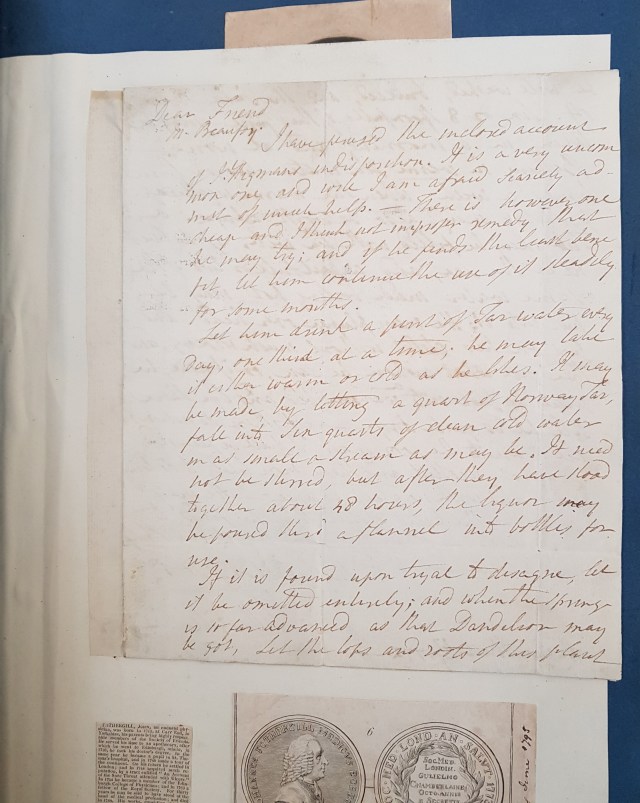

Quakers used their network of connections to gain his advice. In the letter below, Fothergill is replying to his friend Mark Beaufoy, who had forwarded him a letter from William Phillips of Redruth, Cornwall on behalf of one J. Higman. Unfortunately we don’t have the original letter describing the ailment, so we only have Fothergill’s suggested prescription – tar water, dandelion sap and sea-bathing.

Letter from Dr Fothergill to Mark Beaufoy suggesting treatment for J. Higman’s complaint, 1772 (Library ref. MS Vol 337/67)

Like many other 18th century men and women of science, including Quakers, Fothergill was interested in the study of natural history. He collected insects and shells (his collections now form part of the Hunterian Museum), botanical art (his collection was bought by Catherine the Great and is now in Russia), and plants (his herbarium is now in the Natural History Museum). He bought Upton Hall estate in Essex and created an extensive botanical garden, with over 6000 species of plants and a 260ft greenhouse. This garden became what is today West Ham Park.

Plate from The Works of John Fothergill (1784)

His interest in botany led to him being part of a large scientific network that included Sir Joseph Banks, William Hunter and the American founding father Benjamin Franklin. He was elected a fellow of the Royal Society, and sponsored other Quakers in their botanical endeavours. The Library holds several pieces that illustrate this, including a bill from William Bartram for plant collecting on Fothergill’s behalf,

Receipt signed by William Bartram, American plant collector, 1773 (Library ref: MS Vol 337/19)

and the only extant letter by the young Quaker botanical illustrator, Sidney Parkinson, written while accompanying Captain Cook on his first voyage to the Pacific.

Letter to Dr Fothergill from Sydney Parkinson, 1770 (Library ref: Port. 20/46)

Fothergill had sponsored Parkinson, and went to great trouble to assist in the publication of his drawings after his death.

The primary strength of the Library’s Fothergill collections are letters between John Fothergill and his family, most of whom were also Quakers. It is through these letters that we can see the influence of his sister Ann Fothergill on his life. John never married, and Ann moved in with him to look after his three houses. Several of the letters are to or from both John and Ann, and there are also a number of letters by Ann about her brother, particularly following his death, when she was managing the dispersal of his estate.

The Library also holds published works, correspondence, diaries and commonplace books of other members of the Fothergill family, most famously the diary of John’s niece Betty who described her uncle as someone “who delights in making young people chearfull”.

As well as achieving professional success, Dr John Fothergill was “beloved & respected” by those around him. His life was one of energetic engagement in wide scientific and philanthropic affairs of the time, reaching far beyond the confines of his own religious society.

Further Reading

Chain of friendship: selected letters of Dr John Fothergill of London, 1735-1780, ed. Betsy C. Corner and Christopher C Booth (Oxford University Press, 1971) [includes a number of Fothergill’s letters from the Library’s collection]

Hingston Fox, Dr John Fothergill and friends: chapters in eighteenth century life (London: Macmillan, 1919)

Betty Fothergill’s journal, 1769-1770, ed. Elizabeth Francis Diggs (Ph.D. thesis – Columbia University, 1980)

This is fascinating, thankyou!

Dr Fothergill is buried in the Winchmore Hill Quaker Burial Ground in North London. In 1970 the gravestone was given to the Ackworth Quaker School in Yorkshire where it is preserved.

Thank you for the very informative post. I crossed paths with Dr. Fothergill in my research on Mary Morris Knowles, Gender, Religion and Radicalism in the Long 18th century.

Did you find any correspondence to or about Mary Morris Knowles or her husband Dr. Thomas Knowles in the Fothergill collection?

I live in the US but always love to come to London and do research at Friends House Library.

Nothing from or about Mary Knowles, though we haven’t read all the letters. We are always grateful for your Mary Knowles book – and indeed for your kind comments about the library and the blog.

Estoy realizando una investigación sobre la historia de la ventilación mecanica, he leido que el Dr Fothergill fue uno de los primeros que explico sobre resucitacion o administracion de presion positiva en via aerea sin invadirla, lo que hoy seria ventilacion mecanica no invasiva, no tengo mucho mas material y me gustaria si ustedes tienen alguna informacion con respecto a eso, gracias

Thanks for your comment friend. Please email us library@quaker org.uk and we may be able to help.