Our first Quaker Strongrooms blogpost of 2018 is from Ian Watson of Sussex Conservation Consortium, who’s been conserving some of the Library’s “tract volumes”. These are 650 bound volumes of 17th-19th century pamphlets (sometimes grandly described as Sammelbands) – one of the jewels of the Library’s collections. Ian writes about the first stages of his approach to conserving this diverse and challenging material.

Assessing the tract volumes collection

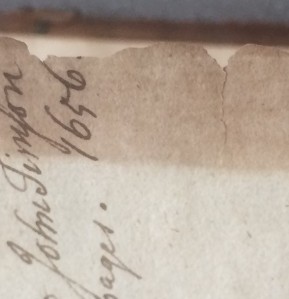

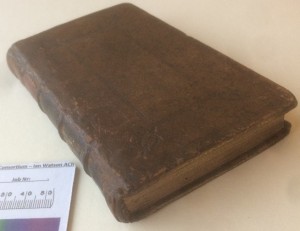

Perhaps the most important stage of conservation occurs before any item arrives at the conservation studio, when we first start to consider its character, importance and condition. So it is with volumes from this collection. The collection as a whole is of high cultural value; the texts are rare; provenance evidence, annotations and marginalia make many of them unique. On top of this, the collection grew in the context of this historic Quaker library. The volumes are important as objects in themselves too – many are early printed works on handmade paper, in contemporary bindings, often in original condition. Overall it is the very definition of a special collection.

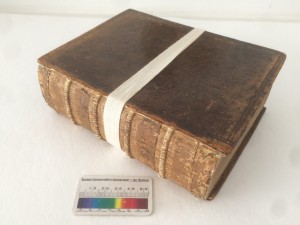

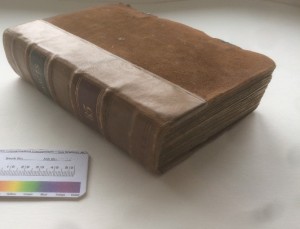

- Why conserve the books at all? Here, Tract Vol 51 has lost its spine leather, exposing the sewing and the spinefolds of the textblock to handling damage and London pollution. In places the sewing has already broken. The binding works but is on the edge of complete failure.

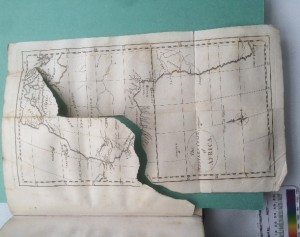

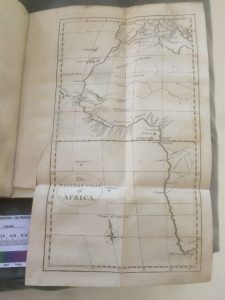

- A map of West Africa in this abolitionist text in Tract Vol 328 is close to being completely lost and cannot be used by readers without risk of further damage, a problem encountered often in this collection.

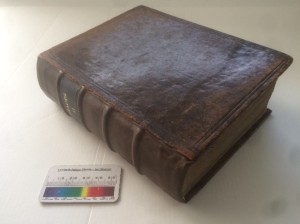

- Some damage is obvious and typical of a binding style or method of manufacture, here Tract Vol 314, a leather tightback binding with a lot of heavy glue on the spine has for years had too much strain on the board hinges, inevitably they weaken and detach.

- Some damage is more subtle, here Tract Vol 85 has had a 20th century repair, a textile tape adhered with glue to hold two leaves together. As the repair has stiffened the paper has begun to split along the edge of the repair tape.

As well as being historically important, the collection is in demand. Yet, as the old bindings become fragile, through handling and environmental pressures, original features crumble. And when they fail outright, text, notes, faint pencil annotations by early readers – those little pieces of history – are all at risk of permanent loss. Thus, the conundrum: the books must be conserved as stable, working objects, repairs need to be made, new material added, originality reduced, but this must be balanced against preserving the collection in as historically original a condition as possible.

Cultural value and future use

Before a conservator can really assess an object, they need to understand its place in the world. Is it rare, unique? Does it get used heavily? What are the plans for its future, exhibitions, digitisation? Who can read it? How is it read – under supervision? With book supports? Where is it stored? What are the conditions there throughout the year? For all this information we conservators rely upon the librarians, archivists, and curators. Without it any treatment proposal is invalid.

What is it made of?

Libraries contain an enormously wide range of materials, from Anglo-Saxon parchment manuscripts to yesterday’s machine pulped, laser printed magazine paper. Just the different types of leather used within this particular collection have required several different approaches to conserve – from fantastically tough Dutch parchment, to extremely fragile English sheepskin, and – perhaps the most challenging to reproduce – suede-like reverse calf.

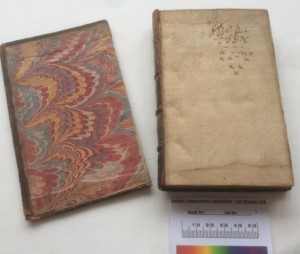

- Tract Vol 136 – a complete and original Dutch vellum binding contemporary to the text within.

- Tract Vol 85 – an 18th century reverse calf binding with a very non-original but well-made 19th century spine, but with substantial losses to the original leather and boards, a real mixture of history and practical conservation problems.

In addition, the volumes cross one of the most important barriers in materials terms: as a collection they date from the 17th to the 19th century: the changes in paper and leather production over this period has profound implications for the collection.

Traditional handmade rag paper, even of poor quality, is a wonderful material – strong, supple and stable; but later wood-pulp paper, which began to be produced in the 19th century, can be acidic, discoloured, brittle, unstable and often unsafe to use without risk of damage.

Vegetable tanned leathers of the pre-industrial period can last for centuries in good condition, whereas some industrial tanned leathers of the late 19th century onwards might only last 50 years before turning to dust due to the chemicals used in the tanning process.

That said, it is never a case of disregarding an object because the materials are of poorer quality, it just means it may be more difficult to preserve it in a stable condition.

How is it made?

Often this can simply mean what type of binding are we dealing with? However, to that must be added – who made it, a master or an apprentice? What was the budget? Was it cheap or built to last? This part of the assessment can often be the most rewarding, especially where the character of the workshop or even the binder themselves can be detected through little tricks of the trade, corrected errors or cost saving methods. As with the materials, it is not the conservator’s place to judge only superior bindings fit for preservation. In my experience, the book historian is just as excited by the little short cuts and developments in style of the low and mid-range bindings as they are by an obviously fine binding.

- The spine of Tract Vol 51 once cleaned revealed some manuscript parchment used by the binder as “waste” to strengthen the headcap and endband (now lost). Some valuable texts only exist because they have been preserved as “binders’ waste” on the backs of later unrelated books. Also note the remains of the green silk endband tied into the parchment.

- Cost cutting – here the binder of Tract Vol 51 has saved a lot of time by sewing the book “3-up” with one stitch linking 3 sections of the text, certainly an efficiency, but not a robust method of book-binding. This is the sort of detail book historians get excited about and which needs to be preserved despite the practical weaknesses they bring to a binding.

What is its condition?

Two copies of the same book printed and bound centuries ago may have had very different lives, and often age and binding style will not be the only indicator of the book’s actual condition. Where has it spent its life? In London during the smog of the industrial revolution? Shelved near a window suffering light damage for a hundred years, or stored in a damp basement, prone to attacks of mould? Has it even been read? Or used to the point of destruction?

- Tract Vol 85 – the flyleaf damage shows where acidic leather from the cover has discoloured the edge of the page, significantly weakened it, making liable to fracture and so putting the manuscript at risk notes at risk of loss.

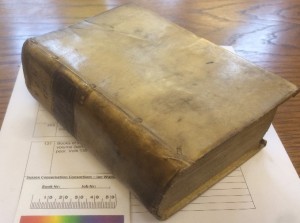

- Tract Vol 393 – whilst still in original condition the spine leather has so deteriorated that it is no longer offering any practical protection to the text or any strength to the binding, yet if this leather is replaced there could be no evidence left of this particular type of basic utilitarian binding left in the collection.

What is important?

In the tract volumes collection, the simpler items to assess are often the well-made bindings in original condition, such as the vellum bound volumes from the personal collection of Anglo-Dutch Quaker William Sewel (tract volumes 131-136). It gets harder where, for example, the book was cheaply made in the 18th century, partly re-bound in the 19th, and then had some paper repairs in the 20th century. Perhaps an original binding isn’t opening properly simply because of a thick layer of poor quality glue on the spine (a common problem). This is where real care needs to be taken when assessing the book and planning the treatment. Decisions will need to be made in conjunction with librarians as to the importance of the item as part of a working collection, and that can often mean the binding must be able to store the information safely, allowing access to text and all the annotations and marginalia in a normal and useful way. However, behind that general rule, all the subtleties of preserving the item’s originality and evidence of its life will have been accounted for and laid out in the treatment proposal. Only when all of that is agreed will the conservator be able to pick up their paste-brush, sharpen their paring knife and begin to treat the object.

Some solutions

- Tract Vol 51 received new sewn silk endbands, the “binders waste” parchment manuscript is still in place and undamaged by the new additions

- Tract Vol 51, with the treatment completed. Though the detail is now hidden by the new leather, the text is once again safe and accessible whilst the historical details on the spine remain in place and have been photographed and reported.

- Tract Vol 328 – with the use of very thin handmade papers made from Mulberry Tree fibres, mainly sourced in Japan, even severe tears to folding maps can be repaired unobtrusively.

- Tract Vol 85 – the missing corners of the board are first built up using layers of acid-free card before being covered with new dyed and shaved reverse calf leather

- Tract Vol 314 – Once the decision is made to intervene, new conservation grade leather joints are dyed cut and pared to fit the original book.

- Tract Vol 314 with the new leather joints in place and back as a working binding with the historical character of the original binding intact.

So far we have had 129 of the volumes conserved (one fifth of the total collection); assessment and treatment of the remainder is continuing. Library users can now read and handle (with care!) volumes that were previously too damaged for use. This work is generously supported by donors to the Library’s BeFriend A Book fund. To find out more or make a donation, please contact the Library library@quaker.org.uk.

I found this article absolutely fascinating. Thank you for its inclusion.

Such complex and important work. The mountain of material needing conservation must seem impossible to climb but thanks for this very interesting blog post.

What an exciting article! I really enjoyed reading it. Thank you for all your skill and care in preserving these precious volumes.

A great initiative and informative article. Thank you. I’m sure that it was a rewarding for both yourself and the participating Library.

Pingback: Some Library highlights of 2018 | Quaker Strongrooms