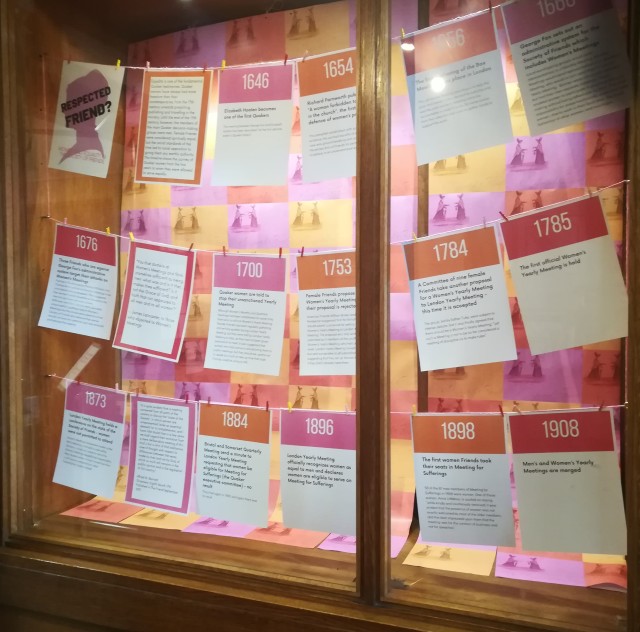

Quaker women in history have a reputation for being bolder and more publicly visible than their contemporaries, being involved with preaching and publishing from the very beginning of the movement. Until the end of the 19th century, however, the members of the main Quaker decision-making groups were men. Female Friends were considered spiritually equal, but there was vocal opposition to giving them any earthly authority. The current display in the library gives a timeline of key events in Quaker women’s history, beginning with the meeting of George Fox and Elizabeth Hooten – considered by some to be the “first definite event in Quaker history” – and ending with the merging of men and women’s Yearly Meetings in 1908.

Library display: timeline of key events in Quaker women’s history

The view that women could speak on religious matters, travel to preach and publish their thoughts was revolutionary in the 17th century when, in some circles, it was taught that women had no souls. It became a defining characteristic of the Society of Friends and intensified their persecution as permitting women to behave in this unconventional way was a very visible difference. Richard Farnworth (1625-1666) published the first written defence of women’s preaching by a Quaker in 1654. This established, using scriptural evidence, the spiritual equality of women. Farnworth’s pamphlet was followed by others, most famously Margaret Fell’s “Women speaking justified, proved and allowed of by the Scriptures” in 1666.

That same year George Fox set out his administrative system for the Society of Friends. Local worshipping groups would send representatives to a Monthly Meeting to handle matters of finance, discipline and membership. Monthly Meetings would send representatives to a Quarterly Meeting, who would in turn send them to London Yearly Meeting, ensuring the Society as a whole was going in the same direction. Women were not usually included in these Meetings, leading to a separate system of Women’s Meetings being developed.

It is generally thought that George Fox had the idea for Women’s Meetings – he certainly promoted them – but evidence suggests that Margaret Fell was central to their establishment. Women’s Meetings were administrative meetings that paralleled, and were subordinate to, the Monthly and Quarterly Meetings. They enabled women to participate in practical decision making without being talked over by men. They had responsibility for areas traditionally associated with women: charity work in their local area, the moral behaviour of other women and marriages.

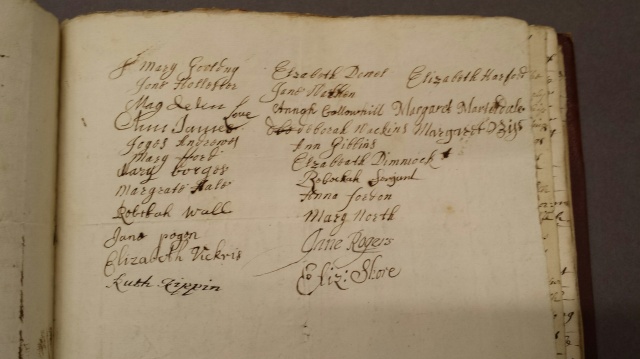

The first all-female Meeting had actually begun a decade prior to this, and formed a pattern for the work done by other Women’s Meetings. London’s Box Meeting had responsibility for helping the poor and needy in the city and its suburbs. It was the only Women’s Meeting not to be accountable to male Friends. Its name comes from the collection box used to gather funds to support the work.

Box Meeting MSS 13 (3)

A group of Quakers led by John Wilkinson and John Story were against George Fox’s administrative system in general, and targeted Women’s Meetings as a focus for their attacks. They considered them to be unscriptural and unnecessary, objected to the women having authority over marriages and suggested that women Friends should leave the work to the men and go home and wash dishes, echoing criticisms of Quaker women from outside the Society.

James Lancaster berated the dissenters “You that stumble at Women’s Meetings and think yourselves sufficient as being men: what was and is it that makes thee sufficient? Is it not the Grace of God, and hath that not appeared to all men and to all women?”

The Wilkinson-Story faction was unsuccessful in putting a stop to women’s meetings, but women’s role in church government continued to be strictly limited, thanks to a combination of contemporary attitudes and fear of criticism from the Quakers’ opponents.

In 1700, although Women’s Monthly and Quarterly Meetings had been established for some time, there was no official Women’s Yearly Meeting. Female Friends had been regularly gathering and writing epistles during London Yearly Meeting, but this year they were told to stop, as they had not been given permission to meet. It was suggested that women who had concerns should take them to a public meeting, although they should be careful not to speak too much or take up time that male Friends could be using to speak.

The women continued to meet in an unofficial capacity and began to work on establishing an official Women’s Yearly Meeting. Much of this work was prompted by American Friends who had Women’s Yearly Meetings already. A proposal was submitted to London Yearly Meeting in 1753, and was rejected, although epistles were sent to all constituent Meetings suggesting they set up Women’s Meetings if they didn’t already have them.

In 1765 the unofficial Women’s Yearly Meeting decided to try a different tactic; they proposed that Quarterly Meetings should report to the official Yearly Meeting on the activities of their Women’s Meetings. This issue was considered “too weighty” to be decided that year, and when it was raised again in 1766 the request was turned down. It was suggested that the informal Women’s Yearly Meeting didn’t have sufficient women Friends of “suitable ability” to carry out the work.

Esther Tuke (1727-1794)

Women were finally given permission to hold their own Yearly Meeting in 1784, when a group of nine women, led by Esther Tuke took another proposal to London Yearly Meeting. It was, however, stressed that “such a Meeting is not to be so far considered a Meeting of Discipline as to make rules”.

This quote highlights two of the issues that Women’s Meetings faced. Firstly, that many male Friends were reluctant to cede any authority to a woman. Anna Price went with Martha Routh to inform London Yearly Meeting of the Women’s Meeting’s deliberations in 1793, and recorded the following:

“a certain young man who was fearful we should be too much set up, and convey too much encouragement to Women’s Meetings. He spoke to M[artha] R[outh] who was a match for him. I said nothing, but was painfully sensible that the life which was in Christ and may also be in us, was not so in dominion in the Men’s Meeting as I thought we had witnessed it. Deep inward wailing and conflict of spirit was much maintained by many through our various meetings, but painful is the jealousy of Men Friends.”

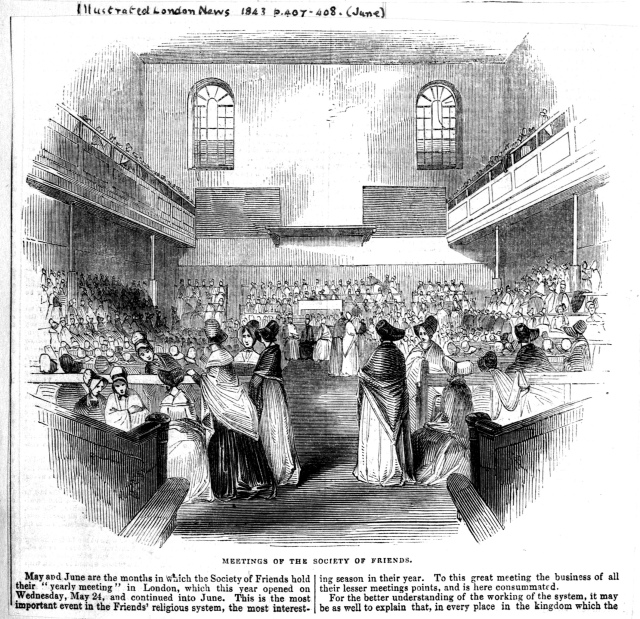

The second issue was that Women’s Meetings actually ended up doing very little. Men’s Meetings continued to make all the decisions, including in areas for which the Women’s Meetings allegedly had responsibility. Many Quaker women viewed the work of Women’s Meetings as “make-work” and chose to invest their time in anti-slavery, temperance or other humanitarian causes instead.

Women’s Yearly Meeting, in Illustrated London News (June 1843)

In 1873 there was a conference held to discuss the state of the Society of Friends. Women were not permitted to attend, a situation which stirred up many heated letters in The Friend, discussing women’s ineligibility for service on Meeting for Sufferings (the Quaker executive body), the fettered nature of Women’s Meetings and correlating the topic with the wider issue of women’s suffrage.

“It is quite evident that a meeting convened from all parts of the country to discuss the “state of the Society”, in which women are unrepresented, lacks an essential element for its completeness; and I have little doubt that in a few years we shall regard their exclusion from a mere deliberative meeting of this kind is but a relic of that barbarous tone of thought with respect to differences between the sexes, made by man and not by God, of which so much still remains in the public opinion and in the legislation of this country”, Alfred W. Bennett, Grasmere, Eighth Month 17th. Published in The Friend September 1873.

Despite this, and two minutes from Bristol and Somerset Quarterly Meeting in 1884 and 1895, it wasn’t until 1896 that London Yearly Meeting officially recognised women as equal to men and declared them to be eligible to serve on Meeting for Sufferings.

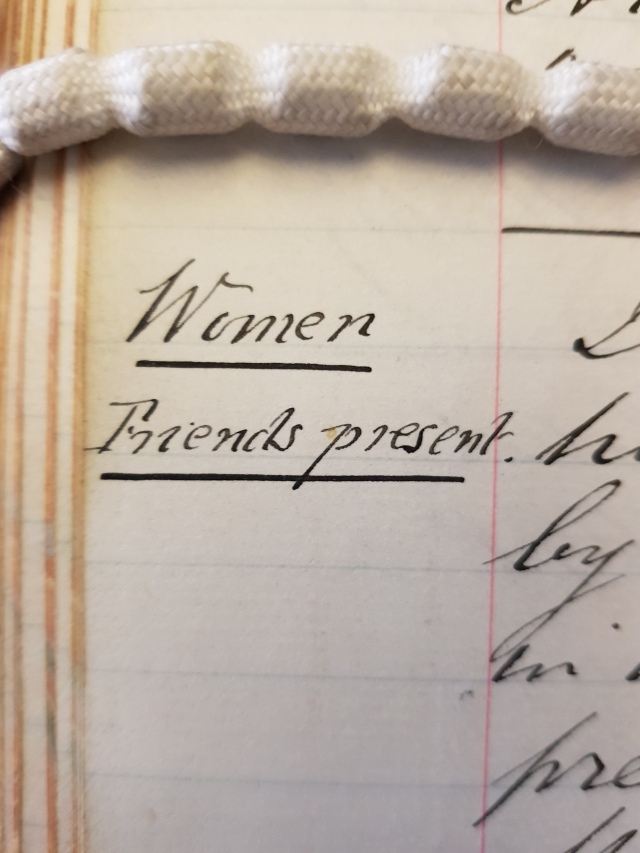

Marginal note in the minutes of Meeting for Sufferings, June 1898

50 of the 87 new members of Meeting for Sufferings in 1898 were women. One of these women, Anna Littleboy, is quoted as saying “while kindly and courteously received, it was evident that the presence of women was not exactly welcomed by most of the older members, and the clerk impressed upon them that the meeting was for the conduct of business and not for speeches”.

Further Reading (all available in the Library)

Bacon, Margaret Hope. “The Establishment of London Women’s Yearly Meeting: A Transatlantic Concern”. In Journal of the Friends Historical Society, vol. 57(2) (1995). Available online: http://journals.sas.ac.uk/fhs/article/view/3499/3450

Britain Yearly Meeting. Quaker Faith and Practice. London: The Yearly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Britain, 2013. Available online here: https://qfp.quaker.org.uk/.

Fox, George. This is an encouragement to all the Womens-Meetings in the world…. London, [1676].

Kunze, Bonnelyn. Margaret Fell and the Rise of Quakerism. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press, 1994.

Martin, Clare J. L. “Tradition Versus Innovation: The Hat, Wilkinson-Story and Keithian Controversies”. In Quaker Studies, vol. 8(1) (2003). Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol8/iss1/1.

Peters, Kate. Print Culture and the Early Quakers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

Pullin, Naomi. Female Friends and the Making of Transatlantic Quakerism, 1650-1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018.

Rowntree, Henry J. “George Fox and Women’s Liberation”. In Friends’ Quarterly, vol. 18(8) (1974) pp.370-376.

Shaw, Gareth. “The Inferior Parts of the Body”. In Quaker Studies, vol. 9(2) (2005). Available online: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol9/iss2/4.

Trevett, Christine. Women and Quakerism in the 17th Century. York: Ebor Press, 1991.

Timeline pack

During Yearly Meeting many Friends requested copies of our timeline display to use in their Meetings. We now have available a pdf pack which includes the display text, some related images and discussion questions. If you would like your free copy of this pack please email us – library@quaker.org.uk – and we will send it to you.

Great post! Would you consider adding the Quaker Womens Group Swarthmore lecture, Bringing the invisible into the light, 1986, pp. 11-20, to your further reading list?

Thanks for the tip Gil – we’ll take a look! The reading list is mostly source material for the blog and display, of course there is lots more reading around Quakers and women’s rights available on our catalogue http://www.quaker.org.uk/cat.

Thanks for this interesting post. But I think the Wilkinson and Story who opposed George Fox’s organisational changes were two Johns, not Thomases. There was a Thomas Story but his was a rather different story.

Hi Derek, thank you so much for pointing out our error, we are somewhat embarrassed! We will make changes accordingly.

Thank you. Great article. Sarah Sheils.

Sent from Yahoo Mail on Android

Thank you for the useful article on Women and Equality in the Society of Friends. I hope to research Mary Katherine Rowntree , wife of Arnold, and this will provide a useful guide.

Pingback: Women’s History Month | Quaker Strongrooms

Pingback: Of Kurds and Quakers – Kurdistan Solidarity Network