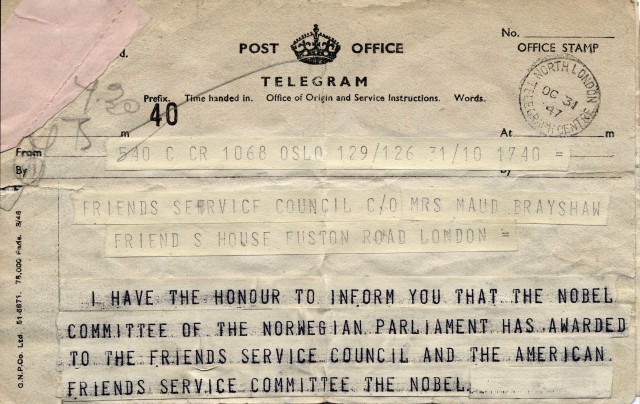

Telegram informing FSC of the award, 31st October 1947 (Library reference: TEMP MSS 54/2)

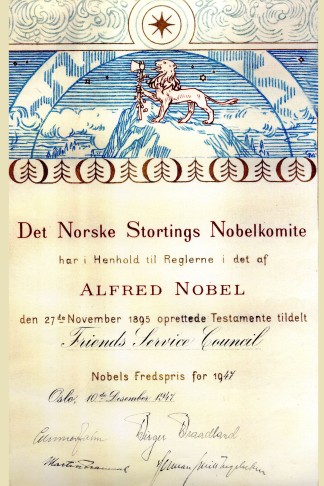

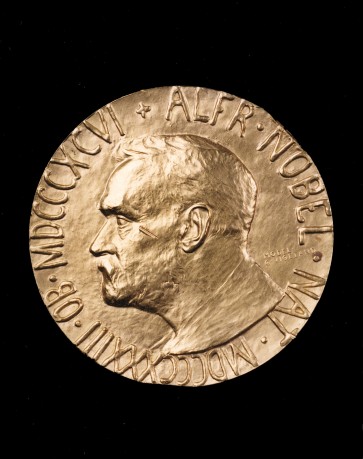

Yesterday marked the the 70th anniversary of the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Friends Service Council and American Friends Service Committee, representing British and Americans Quakers more widely.

The anniversary feels all the more special this year, as the recently announced 2017 winner, International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), is an organisation which represents a cause, the abolition of nuclear weapons, which Quakers have worked on for decades.

Many see this year’s award as a statement from the Nobel Committee on global affairs; a timely message of support for the current UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons; and a boost for pacifist grassroots activism.

In 1947 too, Quakers believed that their award of the Peace Prize should be a stimulus to the ordinary person involved in day-to-day activism. The following two extracts from the acceptance speeches at the ceremony reflect this message:

Today as we live in the shadow of two great wars, we are all conscious not only of the horror of war itself, but of all the aftermath of human misery – starvation, homelessness, and many other forms of physical suffering. We know too of the greater evils of lowered morality, bitterness, violence and self-interest that sow the seeds of misunderstanding and strife. Seeing all this, the Society of Friends is humbled when it realises how little it has accomplished; but the receipt of the award is exhilarating. This recognition of endeavour must serve to stimulate greater effort.

Extract from Margaret Backhouse’s acceptance speech, Nobel ceremony in Oslo, 10th December 1947.

If any should question the appropriateness of bestowing the peace prize upon a group rather than upon an outstanding individual we may say this: The common people of all nations want peace. In the presence of great impersonal forces they feel individually helpless to promote it. You are saying to them here today that common folk, not statesmen, nor generals nor great men of affairs, but just simple plain men and women like the few thousand Quakers and their friends, if they devote themselves to resolute insistence on goodwill in place of force, even in the face of great disaster past or threatened, can do something to build a better, peaceful world.

Extract from Henry Cadbury’s acceptance speech, Nobel ceremony in Oslo, 10 December 1947.

Some Quakers were hesitant about accepting the prize because they generally did not believe ‘prizes’ should be the reward for acting on an inner spiritual belief. This award sat uncomfortably with some, who never sought publicity for their work, which was borne from the core Quaker belief in bearing witness to one’s faith through outward action.

Margaret Backhouse discusses this dilemma in response to a letter from Norwegian pacifist Ole Olden:

I think it is true to say that the Friends Service Council had no hesitation in accepting the award once it had been made. The previous hesitation of Meeting for Sufferings was apparently on the ground of not wishing to seek public recognition of a testimony that lies so closely to our religious conviction.

Margaret Backhouse to Ole Olden, Nov 1947 (Library reference: TEMP MSS 54/2)

She responds to many of the letters of congratulations with repeated mention of her, and the Society’s, embarrassment at the accolade, emphasising the work of other peace churches, pacifist groups, and non-Quakers who worked alongside Friends in war relief work or donated funds towards the work.

Images from our Friends Relief Service (1943-1948) collection

There were some achievements and areas of work that could be seen as quite unique to Quakers at the time though, that may have particularly inspired the award in 1947. One of these was the idea of Quaker International Centres.

Mentioned by Margaret Backhouse in her Nobel lecture (among other specific examples), she highlights the International Centres as an example of work not carried out in response to war, like relief projects, but as positive step towards building a world where war will not take place:

Most of my illustrations have been drawn from the emergency work of Friends, but there are less spectacular outcomes of our belief that all men belong to the family of God. This conviction necessarily leads us to believe that all war is wrong. It is therefore not enough to make efforts to repair the damage that it does, but there must be positive methods used to appeal to the intellectual reasonableness of man. There must be understanding of the problems of relationships, and men must learn to live “in the life and power which takes away the occasion of all wars.

Extract from Nobel Lecture by Margaret Backhouse, Oslo, 12 December 1947.

The concept of Quaker Embassies arose before the end of World War I. Carl Heath and others saw a need for the repair of international relations in Europe and the development of mutual understanding to heal the fractures of war. Many Friends also became unhappy with the Treaty of Versailles, seeing in it the seeds of ongoing hostility between nations. In a letter to Carl Heath a week before the Treaty was signed, Edith Pye says:

“The outlook for the signing of peace seems more and more ominous and the possibility of the renewal of the blockade fills one with horror.”

Letter from Edith Pye to Carl Heath, 11 June 1919 (Library reference: TEMP MSS 54/2)

In 1918, this group of Friends, led by Carl Heath, took the idea to Yearly Meeting, which minuted:

“This concern has taken a strong hold upon the Meeting. We believe there is a call for such a movement not only in Europe but in other Continents.”

Minute 17, Yearly Meeting, 1918

In 1919 the Council for International Service (one of the forerunners of Friends Service Council who were officially awarded the Peace Prize) was set up to undertake the establishment of International Centres, and organise volunteers and staff to work in them. Initially locations were chosen based on cities with strong Quaker links or logistics on the ground. Paris was an obvious first choice: the office that had been used to coordinate relief work expanded its remit to function as an International Centre.

Centres soon sprung up in more European cities: Berlin, Geneva, Vienna and eventually outside of Europe also.

The centres provided meetings for worship, study groups, cultural activities, and space for other organisations and community groups to meet. They aimed to forge community and political links, offer places of support for Friends ‘in transit’, and support local Quaker meetings where they existed. The concept was described as a ‘ministry of reconciliation’, a phrase repeated by Henry Cadbury in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Peace Prize.

In the lead up to World War II, the centres in Paris, Geneva, Vienna, and most importantly Berlin, were increasingly involved with fostering reconciliation and peace, and dealing with the unfolding political situation.

The Berlin Centre became very active after Hitler came to power in 1933, supporting persecuted groups including pacifists and socialists whom Hitler sought to purge from society to strengthen his political control over the country. The Berlin Centre already had strong links with these groups, and indeed some individuals involved were Quakers themselves.

The staff at the centre visited people in prison and pressed for their good treatment and release, even at personal risk to themselves. Corder Catchpool, the Quaker warden of the Berlin Centre, was himself arrested, as were German Quakers such as Leonhard Friedrich. It was information gained through the work of the centre that led to British Friends’ recognition of the urgency of the situation and the establishment of the Germany Emergency Committee in 1933. This would become the Friends Committee for Refugees and Aliens, which eventually assisted almost 2,000 people to escape Nazi persecution.

In this way, ongoing, small-scale ‘peacetime’ activism fed into the success of large scale wartime projects. It may be the wartime projects that garnered attention and praise but they would not have been possible, or as successful, without the hard work in the years before the war.

This is just one example of the type of peace witness work Quakers undertook. It was Quaker service of this kind that appealed to the Nobel Peace Prize Committee and led to the award of the Nobel Peace Prize in 1947.

To find out more about the current work of Quaker Peace and Social Witness (the successor body to Friends Service Council), visit the Quakers in Britain website: http://www.quaker.org.uk/our-work

Reblogged this on hungarywolf.

Pingback: 70th Anniversary of Quakers and the Nobel Peace Prize | Swiss Quakers

Reblogged this on catsissie.

Pingback: A year in view: Quaker Strongrooms blog 2017 | Quaker Strongrooms

Pingback: Quaker feeding programmes in postwar Germany and Austria | Quaker Strongrooms