Most of the men who found themselves imprisoned for conscientious objection during World War I were characterised as absolutist objectors. These men were not willing to participate in the war effort to any extent, turning down non-combatant duties and alternative work which would contribute to the war effort. The absolutists primarily consisted of members of the No-Conscription Fellowship, formed by Clifford Allen and Fenner Brockway, members of the Independent Labour Party and other socialist groups, Quakers and members of other religious bodies such as the Jehovah’s Witnesses – or indeed those who counted themselves as members of more than one of these groups.

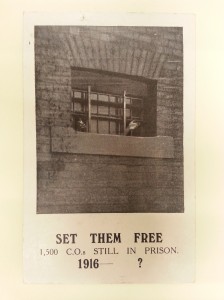

“Set them free”. Postcard, unknown source, undated [1916-1918?]. Part of Rowland Philcox Papers (Library ref. TEMP MSS 197/5)

The Winchester Whisperer, the clandestine prison newspaper written by COs in Winchester Prison, has been getting a lot of attention recently in the media and rightly so – you can read an article about it here.

However, there are other less well known collections which paint a fuller picture of what life was like for imprisoned COs during the war. You can see a list of some of these collections in our subject guide on Conscientious objectors and the peace movement in Britain 1914-1945, available on our website here: http://www.quaker.org.uk/subject-guides.

To highlight the collections we can look at some common themes which emerge from the material, mainly contemporary correspondence and diaries.

A challenge to the authorities

The absolutists really challenged the government’s enforcement of the Military Service Act and the procedures in local and central tribunals, military courts, and civilian prisons for dealing with these men. This is reflected in the manuscript collections as the men describe their treatment, being passed from pillar to post through the civil and military courts systems, from barracks, to civilian prisons, and to work camps. The initial attitude taken by the authorities is described by Cornelius Barritt (1883-1967):

“In the evening an officer visited me in my cell and asked ‘How long are you going to keep this up, you belong to King and country now and must do as you are told’, to which I answered ‘I shall keep this up as long as strength is given me to do so'” (Cornelius Barritt, Diary while in the hands of the military. Library ref. TEMP MSS 62/MISC/DIA/1)

Barritt was first tried in March 1916, then taken to France where he was brought before Field General Court Martial and sentenced to death on the 10th of June, later commuted to ten years penal servitude. He spent time in Winchester Prison, before being sent to work camps in Dyce and Wakefield. As an absolutist, he refused to participate in the work scheme and was sent back to Maidstone Prison, where he remained until 1919.

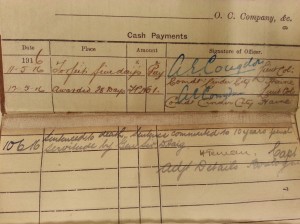

Cornelius Barritt’s ‘soldier’s pay book’ showing his sentence: “Sentenced to death. Sentence commuted to 10 years penal servitude by General Sir D. Haig” (Library ref. TEMP MSS 62/COR/LT/4)

The government seemed to underestimate the power of these men to stick to their principles, and many of the collections describe soldiers, prison guards and judges gradually coming to respect the strength of those principles.

This recognition and ceaseless campaigning on their behalf led to attitudes softening somewhat in some government circles, and much debate in the cabinet over their treatment. Some COs were released in 1917 on medical grounds and certain privileges were granted to them in prisons.

As well as challenging authorities, the COs found it somewhat a challenge to organize a common strategy among them, as their ideas on the forms of objection differed and changed throughout the war. This is well reflected in the letters of Roland Philcox (1877-1965) and Joseph C. S. Elliott (TEMP MSS 197), who were active in the No-Conscription Fellowship and described in detail the range of attitudes of the men they encounter in prison. Philcox shows the uncompromising attitude some of the absolutists adopted:

“These N.C.C. [Non-Combatant Corps] men reported themselves in the ordinary manner, they are quite willing to do work but not killing. They are the shirkers and have let us down, for we stickers out are in a minority.” (Library ref. TEMP MSS 197/1)

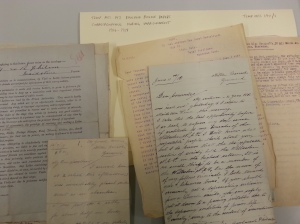

Correspondence from Rowland Philcox during his imprisonment as a conscientious objector, 1916-1918 (Library ref. TEMP MSS 197/1)

A new generation of prison reformers

Another common thread running through the personal accounts of imprisoned COs in World War I is the insight into prison conditions they gain from their time in civilian prisons and how this develops into an interest in prison reform – carrying on a strong Quaker tradition.

Many of them describe in detail the difficulties of solitary confinement, poor sanitation, limited opportunity for conversation with fellow inmates, and – a constant feature in all the accounts – prison food, with Philcox (a vegetarian) even including a handwritten menu for Maidstone Prison! (Library ref. TEMP MSS 197/1)

Elliott, who rarely complains about prison conditions, describes an encounter in Mountjoy Prison to illustrate the attitude of the clerk, but it shows the toll the experience has taken on him physically:

“Just then another clerk said ‘You lost some weight in here!’ So the clerk said sneeringly:- ‘Yes that’s his disobedience; he would not have lost 3 stone if (he) did what he was told.’” (Library ref. TEMP MSS 197/2)

The men were often on punishment diet of bread and water for refusing to undertake tasks they felt conflicted with their beliefs.

The ultimate sacrifice

What emerges most strongly from the accounts and correspondence of these men is the strength of their conviction. They speak passionately and intelligently about their reasons for opposing the war.

Philcox expresses the strength of his conviction eloquently in an early letter when the men are being threatened with the death sentence in France:

“I expect my comrades at liberty are agitated by the news of our probable fate, but I suggest that they do not devote all their efforts to procuring our release. Remember that the ideas of patriotism and militarism are surrounded with the glamour of self-sacrifice which the heroism of innumerable soldiers has cast upon them – sacrifice hallows any cause…When the final hour arrives…the principles of International Fraternity will be placed on an equal footing to the prejudice of patriotism.” (Library ref. TEMP MSS 197/1)

In the papers of Arnold Rowntree MP (1872-1951), there is an extreme example of the hardship endured by C.O.s – a vivid demonstration that the path of the absolutist was not an easy one, taken by cranks and shirkers. The account tells how H. Firth arrived at the Dartmoor work camp malnourished after spending 8 months in Wormwood Scrubs and Maidstone Prisons. The men appealed on his behalf, on seeing his weakened state, but he was immediately put onto heavy quarry work. After one collapse, they moved him on to ‘whitewashing’ which was done through the night, from 7.30pm to 5.30am. He eventually ended up in the camp hospital after another collapse.

The account recalls:

“He was in a very emaciated condition and complained then and repeatedly of great weakness and thirst….On January the 8th he again applied to the doctor, complaining of the cold, and was met with the usual taunt that it was selfish, and that the soldiers in the trenches had to put up with worse

…

On that day he (the doctor) met Firth’s request for eggs for food with the remark that they were all needed for wounded soldiers. Three eggs arrived the next day when Firth was dead, for he died at 8.55 am on Wednesday morning, February 5th. The previous evening, a friend suggested that Firth’s wife should be telegraphed for, but the doctor replied that it was quite unnecessary. Death was due to diabetes .” (Arnold S. Rowntree Papers, Correspondence with conscientious objectors. Library ref. TEMP MSS 977/2/12)

The brief selection of highlights above just starts to scratch the surface of the amount of material we have which really gets inside the minds of conscientious objectors and makes their prison experiences vivid for today’s researcher.

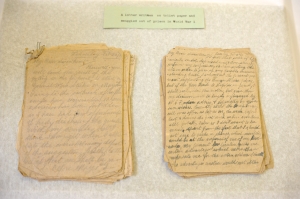

Letter written on prison lavatory paper by Rowland Philcox and smuggled out of prison. Part of Rowland Philcox Papers (Library ref. TEMP MSS 197/1)

Excellent blog. Please remember that C.O.Day is Thursday May 15th, and will be celebrated by a meeting in Tavistock Square. Anne Driver

My grandfather was a conscientious objector in WW1 .He was a truly gentle man and like all the other conscientious objectors a man of peace,who stuck to his belief ,.I think these people were incredibly brave to stand up to a government who considered life to be cheap . Just what for ? Not even an inch of land.We must always remember them along with all those of all nations who died in the cause of peace

Pingback: Library resources for researching World War I: Wartime Statistics Committee | Quaker Strongrooms

Pingback: Quaker Strongrooms blog at the turning of the year | Quaker Strongrooms

Pingback: War and social order | Quaker Strongrooms