Quakers in Britain have committed to making practical reparations for the transatlantic slave trade. In November, as part of an event organised by London Quakers to explore what reparations might look like, the Library welcomed Friends into the reading room to learn about four London Quakers who were involved with, or profited from, the enslavement of Black Africans. These are their stories.

John Rous (c.1630-1695)

John was born in the parish of St Philip, Barbados in the 1630s, the son of a sugar planter Thomas Rous. He joined his father and brother in the sugar business, the three of them jointly owned a large plantation and by 1680 were enslaving 310 people.

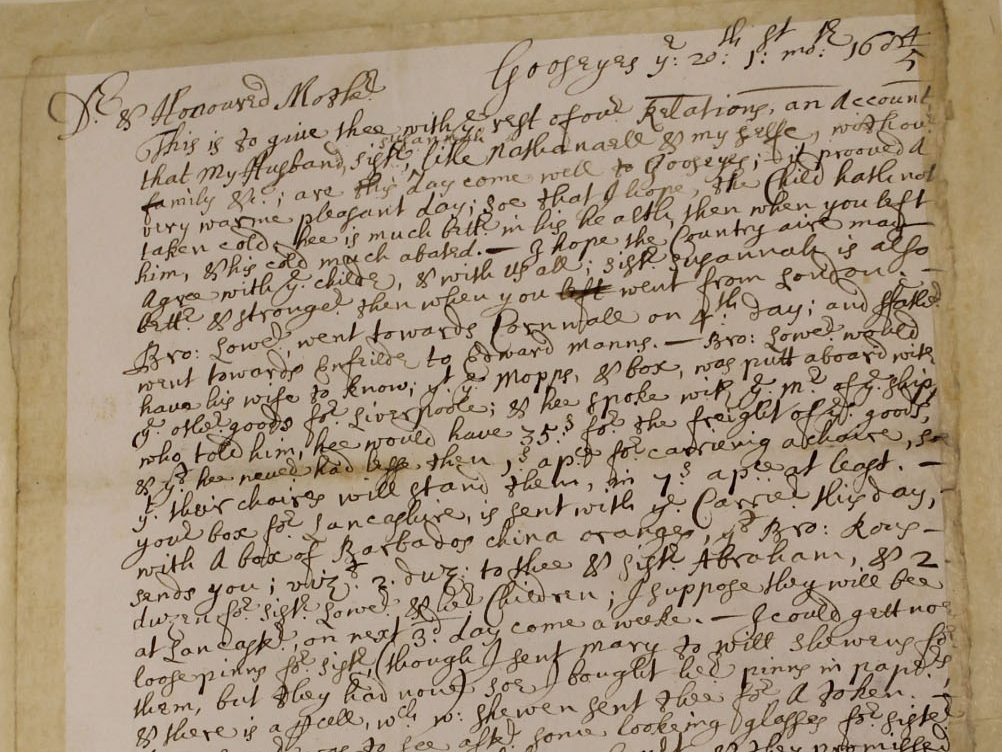

He became a Quaker in the mid 1650s after encountering missionaries Ann Austin and Mary Fisher. After corresponding with early Quaker leader Margaret Fell some time, he sailed to England in 1659 where he met and married Margaret’s eldest daughter, Margaret Junior, at Swarthmoor Hall.

John and Margaret Junior settled in London, going on to build a large house in Kingston. John remained involved in the business of his plantation, setting himself up as a West India merchant at the Bear and Fountain, Lothbury. He acted as an agent for his father and brother and frequently travelled back to Barbados.

John was an important part of the Fell family, and a weighty Friend. There are letters in the Swarthmore Documents describing his sending sugar and Barbados oranges up to Swarthmoor Hall. He travelled with George Fox to Barbados in 1671, and they stayed on his plantation. He also contributed significantly to his local meeting, donating £30 towards the building of the meeting house (the equivalent of a year’s wages for a skilled tradesman).

John was known to advocate for kind treatment of enslaved people, but he doesn’t appear to have made any moves to free those on his plantation. He died on a voyage home from Barbados in 1695.

James Claypool (1634-1687)

James was the fifth son of a wealthy family from Northamptonshire. His older brother John was married to Oliver Cromwell’s favourite daughter Elizabeth. He made his money as a factor, or agent, for overseas producers. One of his key business partners was another of his brothers, Edward. Edward Claypool owned a 325 acre sugar plantation in Barbados. According to the 1680 census, there were 86 enslaved people and 12 indentured servants on his plantation.

James appears to have become a Quaker by convincement in 1660 and he and his family attended several meetings, including Bull and Mouth and Devonshire House. He became very influential, serving on Meeting for Sufferings, Six Weeks Meeting (now known as London Quaker Property Trust) and Morning Meeting, the committee who decided which Friends got their works published. He also made various donations to meetings, including 10 shillings towards the building of Cobham meeting house and £2 towards the general accounts of Six Weeks Meeting.

It is alleged that James was miraculously healed by George Fox. The pair were visiting Guilielma Penn when James became ill with kidney stones. George laid hands on him and his kidney stone “came from him like dirt”.

In 1682, James decided to emigrate to Pennsylvania. He wrote to his brother Edward asking him to provide “2 good stout Negro men, such as are like to be pliable and good natured” and “a boy and girl to serve in my house”. He continued to do business at home via his former apprentice Edward Haistwell (c.1658-1709), who is perhaps better known as one of George Fox’s secretaries and travelling companions.

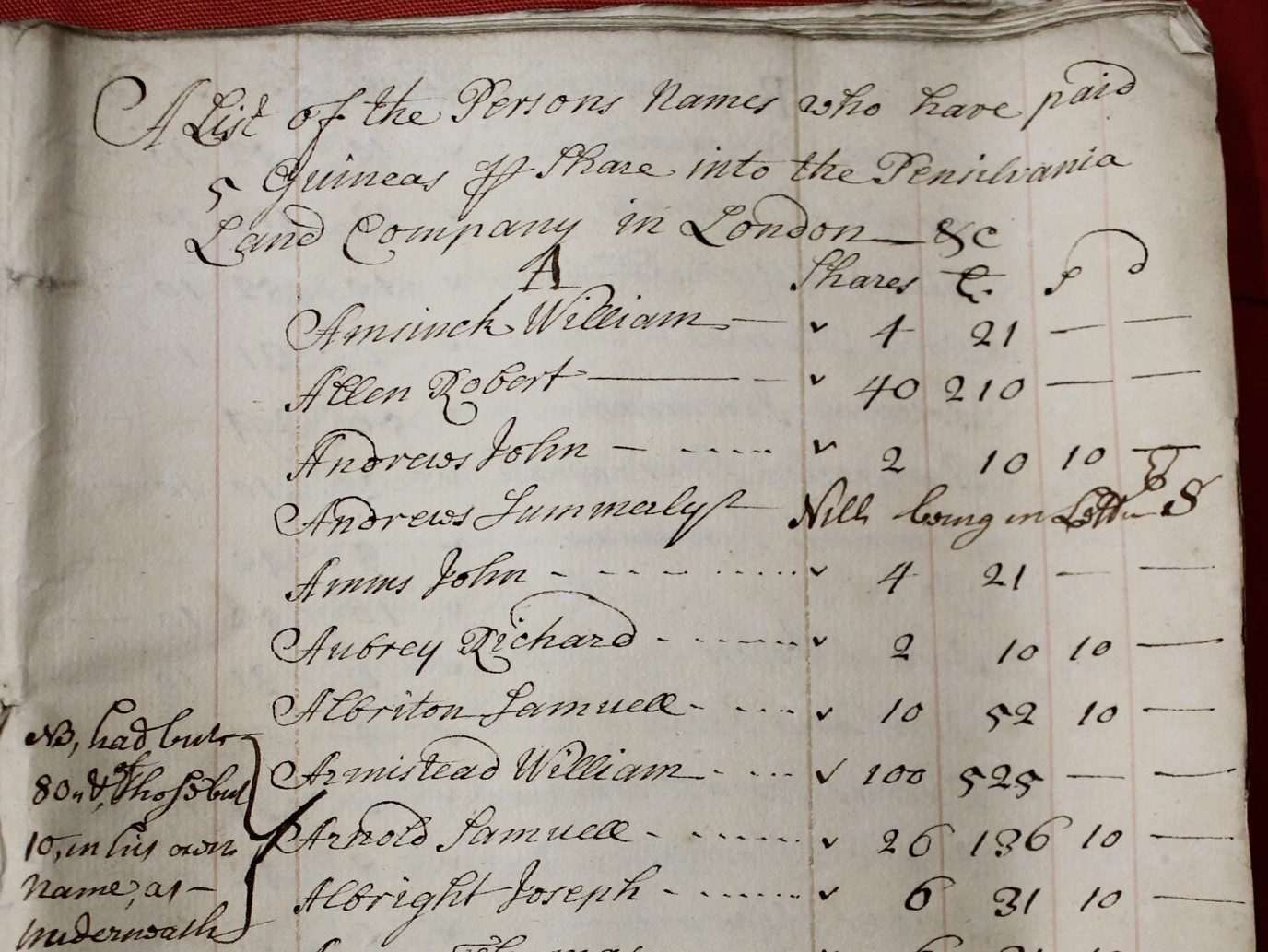

The Pennsylvania Land Company

The Pennsylvania Land Company was a colonial joint-stock company based in London and primarily operated and funded by Quakers. The treasurer was Thomas Story (1662-1742) and investors included David Barclay (1682-1769) and recording clerk Benjamin Bealing (d. 1739). Its business was buying land in Pennsylvania to grow flax, which was then used to supply the British Navy.

A scandal occurred in 1720, when James Hoskins, a Quaker and investor in the company, took the company’s capital and invested it in the South Sea Company. The South Sea Company was another joint-stock company. Part of their business was supplying enslaved Africans to South America. Although this was not considered a financial success, investment in the company allowed it to transport just over 34,000 enslaved people across the Atlantic, with a mortality rate of 11%. Other Quakers who are known to have invested in the South Sea company include John Freame (founder of Barclay’s Bank and listed as a proprietor of the Pennsylvania Land Company) and Theodore Eccleston (a weighty London Friend).

Unfortunately for James Hoskins, he invested all the Pennsylvania Land Company’s money at the height of the South Sea Bubble. The South Sea Company’s share prices were overly inflated, leading to a financial crash in August of that year. James Hoskins and Thomas Story argued over whose fault this had been, resulting in James disownment from the Society of Friends. The South Sea Company’s slave-trading was not an issue, but James was considered to have acted dishonestly and greedily.

Thomas Corbyn (1711-1791)

Thomas was born into a Quaker family in Worcestershire. He moved to London to apprentice as an apothecary, later taking on his mentor’s business. His company primarily manufactured pharmaceuticals wholesale, becoming known for quality. He utilised the Quaker’s reputation for honesty to enhance his business dealings and was very successful.

Thomas was known for being a severely plain Friend, receiving the nickname “Pope Corbyn”. He attended Peel Meeting in Clerkenwell, to which he made donations of around £10 a year, and served on Meeting for Sufferings and Six Weeks Meeting.

Corbyn & Co. did significant trade with the British colonies in the Caribbean and North America, supplying plantations with medicines and in turn purchasing their sugar, cotton and medicinal plants. Due to lack of local supply, extensive imports of medicine were essential to keeping the plantations going.

A study by Carolyn Elizabeth Roberts found that Corbyn also produced medicines for at least three major slave trade suppliers. Harrowingly she argues that at least some of these medicines were used to subdue enslaved people aboard the ships.

“If one were to peer more closely at the specific drugs and their quantities, the researcher might ask why there were as many as 3,840 doses of pure opium on a ship carrying 225 people, for a voyage that lasted a total of seven months… Like the rigging that was erected to prevent captives from jumping overboard and the large crews that merchants hired to maintain surveillance, forced drug consumption was considered necessary to preserve the health and lives of captive Africans.”

“Pharmaceutical Captivity, Epistemological Rupture, and the Business Archive of the British Slave Trade” by Carolyn Roberts

These four stories are a brief glimpse into how London Quakers, like many others of their time, profited from colonialism and enslavement. In the 18th and 19th centuries London was the biggest port in the world and until 1730 it was Britain’s largest slave port, with around 50 slave ships setting out per year. The merchants of the city made a thriving trade in products such as sugar, tobacco and cotton. In addition to this, London is Britain’s financial centre, and it was here that Barclay’s bank, for many years a Quaker institution, was founded. There is lots of work to be done if we are to have a true understanding of the creation of our inequitable world and take reparative action.

If you would like to find out more about Quaker work around reparations visit the reparations resource page here: https://www.quaker.org.uk/resources/reparations

Additional Reading

Balderston, Marion (Ed.) (1967) James Claypoole’s Letter Book: London and Philadelphia 1681-1684. San Marino: The Huntingdon Library.

Beales, Kristen and Consenstein, Eden (2021) “Time Incorporated and the Pennsylvania Land Company” in The Immanent Frame. Access online here: https://tif.ssrc.org/2021/05/14/time-incorporated-and-the-pennsylvania-land-company/

Dunn, Richard (1972) Sugar and Slaves: the rise of the planter class in the English West Indies, 1624-1713.

Hotten, John Camden (1874) The original lists of person of quality…[contains a partial transcript of the 1680 Barbados census]. London: John Camden Hotten. Access online here: https://archive.org/details/originallistsofp00hottuoft/page/n5/mode/2up

Roberts, Carolyn Elizabeth (2017) To Heal and to Harm: Medicine, Knowledge, and Power in the Atlantic Slave Trade. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Access online here: https://dash.harvard.edu/handle/1/42061516

You can find additional sources of information on this topic on our digital resources page here: https://raindrop.io/Library_of_the_Society_of_Friends/slavery-and-abolition-21701511

Dear Quaker Strongrooms

Thankyou for sending this most fascinating blog, surprising but not surprising really in the grand scheme of things. The email has come at an opportune moment as we are considering a suitable repository for a particular document.

My husband has a original handwritten document from 1823 concerning the manumission of a slave named Paulo Africano in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in both English and Portuguese. We are looking for a permanent home for it and I wondered what is the legal position of documents held by the Society of Friends? I am mostly concerned about documents being sold in the event of some catastrophe, we are living in precarious financial times.

PA travelled to England with his ‘sponsor’ Thomas Gibbins 1796-1863 who later married Emma Joel Cadbury 1811-1905. The Cadbury link means I will be contacting Cadbury repositories and the Birmingham Record Office and asking similar questions. We are intending to donate the document.

Thank you for your time reading this through.

Please email or phone me for further information.

Best wishes

Louise Perrin & Julian Fox

Thank you very much for your kind offer. Would you be able to email this enquiry to library@quaker.org.uk and our archivist will be able to discuss this with you?